You peruse your bookshelves1, looking for something to read, when a thought occurs to you. You’ve read many books with third person perspective. Indeed, that seems to be the standard. First person narratives abound as well2, particularly in detective-adjacent stories. But what about second person? Wouldn’t it be easier to identify with the protagonist if the text suggested that the reader is the protagonist?

Writers must disagree, for there are relatively few examples. However, with some thought, you come up with five, that most perfect number of examples3. However, one of them suggests a bold narrative structure that will almost certainly break the Reactor website. The prospect of weeping web admins is too delightful to resist. Setting that example aside for now, you settle for four…

Well, why not? Readers are unlikely to notice unless you draw attention to that detail, and you can always remove any such admission before sending off the file. While you did intend to remind yourself not to highlight your deviation in this matter, you are distracted by a rabbit outside the dining room window. You never write the note. It is a very adorable rabbit.

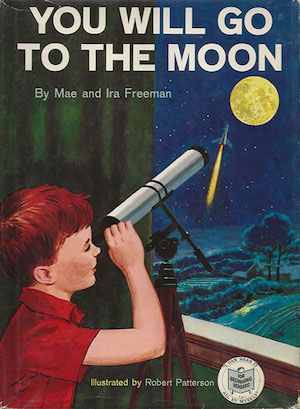

You Will Go to the Moon by Mae and Ira M. Freeman (1959)

You remember fondly this children’s classic of space exploration, almost as old as NASA itself. Aimed at young readers, it delivered its essential space travel concepts to you in vocabulary appropriate for first graders, with illustrations on each page to further entice its target market. Given how often you reread it as a child, the design succeeded in its purpose.

Turning the pages, you consider what aspects of a lunar trip the Freemans got right—the need for a multistage rocket—and how many of the details did not play out as envisioned in the 1950s. In particular, rotating space stations are an as-yet unrealized potential4.

Still, you are bothered by the possibility that this book is not quite true second person. The phrasing suggests an adult is relating the events to come to a child before dispatching it into the icy depths of endless space, never to return. Are there better examples?

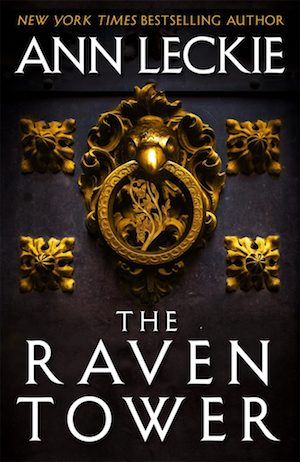

The Raven Tower by Ann Leckie (2019)

The Strength and Patience of the Hill is a god, old enough to remember trilobites. Despite this vast perspective, it chooses to focus on a small, very recent series of events. These involve power politics amongst the bipedal primates who recently evolved, their effect on Mawat, and Mawat’s friend Eolo.

Mawat, a prince of his people, believes that his father was murdered so that his uncle could take power. In fact, while Mawat’s uncle is indeed a miscreant, the crimes being committed are far more ominous than a simple assassination. Mawat’s misapprehension and the actions he takes as a consequence have divine implications. Tragedy for some, but not for The Strength and Patience of the Hill.

Have you ever provided a list of Hamlet-influenced works, you wonder? This question is a welcome distraction from the cold fact that this example too is not quite what you had in mind. Some sections of the narrative are second person, but others are first. Clearly Leckie did not consider your current needs.

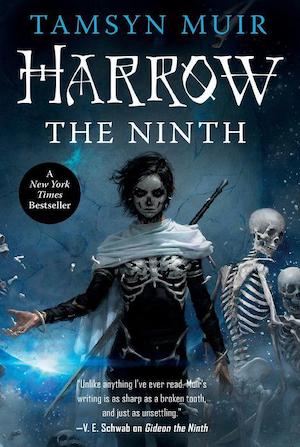

Harrow the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir (2019)

You discover that having entertained readers with a snarky, straightforward first person account in Gideon the Ninth, Muir shifts her perspective to Harrowhark “Harrow” Nonagesimus and her preferred tense to second in the sequel. Harrow ascended to the status of Lyctor at great cost to Gideon. You are not surprised to discover that surprises await…or why would there be a sequel?

In fact, a glorious assortment of surprises awaits both Harrow and you, as Harrow’s recollection of events is both incomplete and hard to reconcile with the first volume. Clearly, the author is working towards a goal visible to her, but initially not to the reader. Confused but intrigued, you persist.

In what is becoming a recurring pattern, you notice that this example too does not quite fit the remit. Harrow the Ninth is not entirely second person. Some portions are third person. You consider whether you should have researched more diligently, rather than acting in your usual haste. You are comforted by your conclusion that fault must lie with either Senator Proxmire or the Thor Power Tool Decision, as they are the sources of all evil in the world according to top SF pundits. Onward!

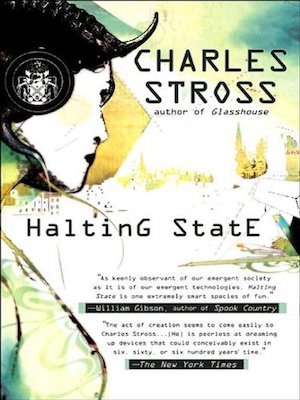

Halting State by Charles Stross (2007)

The narrative draws your attention to three protagonists, police person Sergeant Sue Smith, programmer Jack Reed, and forensic accountant insurance fraud investigator Elaine Barnaby. The tale cycles through each protagonist’s perspective.

At the center of the plot is Hayek Associates, a company that is the victim of a cybercrime. Ideally, crimes should be straightforward to resolve. This one is not. This is unfortunate, as the stakes are far higher than is at first apparent.

You note the care that Stross takes to make each perspective easily distinguished from the others, and the determination with which he stuck to second person. You also dwell upon on how swiftly and comprehensively actual near-future history diverged from Stross’ speculations. How sunnily optimistic SF authors were, nearly twenty years ago. Nevertheless, Halting State is exactly what you had in mind when you began, and you type the final period with satisfaction.

Could you round out the numbers to five by discussing Rule 34, Halting State’s sequel? You would have to mention two works by the same author in one essay not specifically devoted to that author. This feels like cheating. You set Rule 34 aside for an essay about novels set in the 2020s. You feel smug that in the course of writing this essay, you thought of ideas for three more. You prudently decline to consider how few of your idea seeds eventually become finished essays.

You realize that this leaves the matter of comments. Readers being so many and so widely read, no doubt they will immediately think of the examples you might have mentioned5. Best to admit personal flaws and await illumination.

Will commenters frame their comments in the standard format or will they use second person? You conclude there is no way to find out except to wait and see.