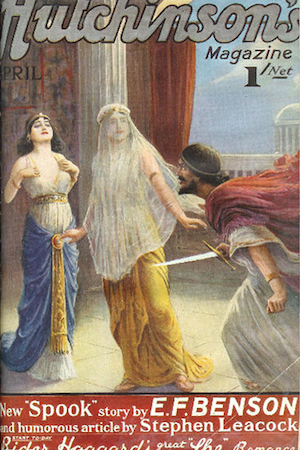

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover E. F. Benson’s “The Outcast,” first published in Hutchinson’s Magazine in April 1922. Spoilers ahead!

Tony and Madge Carford live in the “lively little town” of Tarleton. Nearby is the Gate-house, unoccupied since its last tenants left after one month. During the Elizabethan persecution of Catholics, two brothers lived there. The younger betrayed the elder as a Papist. The elder died on the rack. The younger hanged himself in the house’s parlor, where his apparition supposedly appears.

When Bertha Acres settles in the Gate-house, her tragic history precedes her. Her young husband Horace Acres loved her fortune, not her. After their marriage, his indifference inexplicably turned to hatred and dread. He begged for a divorce, but the devoted Bertha refused. Horace shot himself. He left a note stating, “The horror of my position is beyond description and endurance. I can bear it no longer: my soul sickens…”

Madge calls on Bertha, finding her handsome, cordial, and witty. But Madge’s enthusiasm turns to perplexed silence. She confesses that while Bertha remained altogether agreeable, she was chilled by a moment of giddy horror after inviting the widow to dinner the next evening. Tony, knowing Madge is sensitive to psychic phenomenon, suggests that perhaps it was the “haunted” parlor that upset Madge. Madge gladly accepts this explanation, determined to like Bertha.

Tony goes out to post a letter. He observes a stranger and realizes she must be Bertha Acres. Odd, how he felt momentary unease when they passed each other, like Madge’s “sickness of the soul.” Later he’ll remember that Horace Acres’ suicide note similarly described his spiritual state.

Charles Alington, Madge’s brother, arrives. He’s “the happiest man” Tony knows, since all his energies are focused in inquisitiveness, and all his inquisitiveness in the realm of the yet unproven. Reincarnation is his latest passion. But what a blessing that we don’t recall our past lives! Imagine Cleopatra trying to tolerate an ordinary life, or knowing that you were Judas Iscariot!

Bertha arrives, and Tony finds her attractive, with features “slightly Jewish” or “Eastern”. But the Carfords’ normally-friendly bulldog flees. Bertha sighs: dogs are always terrified by her.

Bertha is charming at dinner, seemingly unaware of the withering effect she has on Madge and Tony. Charles, however, appears intellectually entranced. He asks if Bertha’s comfortable at the “haunted” Gate-house. She replies that she finds its atmosphere “peaceful and homelike”—any ghosts must be sympathetic! Later Charles wonders: Given that the Gate-house ghost betrayed his brother, what could it mean for him to like Bertha?

Other neighbors’ reactions mirror Madge’s. They start out singing Bertha’s praises, then fall into uneasy silence. Other animals act as Fungus did. People, being civilized, hide their dread, but a blight hangs over any gatherings Bertha attends or hosts. Madge is determined to go to Bertha’s Christmas party, but sudden illness keeps her away. Soon after, Bertha departs for a trip to Egypt

Easter approaches, and Charles visits again. He’s “humourously” disappointed to find Bertha gone abroad. It’s he who sees the newspaper notice that on the Thursday before Easter, Bertha died coming home and was buried at sea. On Easter afternoon, Tony goes to golf and Madge to walk on the seashore, the vague darkness that’s hung over her having lifted since the sadly welcome news. Midgame, Tony’s called back to the clubhouse—Madge has discovered a body washed up on the sand. It rolls over in its canvas-sack shroud, to show her Bertha’s face, eyes open. There’s something awful in the way “the sea won’t suffer her to rest in it.” Tony wonders what strange chance brought the body back home.

After an inquest, Bertha lies coffined in her parlor. Madge sends Tony with a wreath of fresh flowers. He lays them on her coffin and watches them wither at once. Only Tony, Madge and Charles are mourners at her funeral. It’s found that the grave isn’t long enough and must be redug. Madge sobs, “And the kindly earth will not receive her.”

Afterwards Tony walks, fighting a fantastic conviction compounded of Madge’s sobbed words and Charles’s belief in reincarnation. Instead of following the road back into Tarleton, he takes a shortcut through the cemetery. He needs to see that the gravediggers have done their job properly. They have. He’s turning away when the mounded earth starts rising as if pushed from beneath. He hears wood breaking; when the head of the coffin emerges, the shattered lid reveals Bertha’s wide eyes.

Tony runs in panic. Together with the parson, Charles, and the undertaker’s men, he returns to the gravesite. Bertha’s coffin lies completely disinterred. The next day, her body is cremated.

Tony has no explanation for these events. Charles isn’t so thwarted. He sends Tony a medieval treatise on reincarnation. One quotation claims that “he” has been reincarnated multiple times. Once was as a man buried at sea only to be cast back ashore, another time as a woman fair and pleasant who nevertheless inspired horror. She is said to have died on the anniversary of his suicide following the betrayal; though buried deep, the earth spewed her forth again. At length his expiation will come, and whichever body holds his accursed spirit will be purged with fire. Then he will have rest, and “shall wander no more.”

The Degenerate Dutch: The Ango-Israelites—at their peak at the time of Benson’s writing but still around—manage to combine antisemitism with imperialism, white supremacy, and heresy.

Souls are genderless, but being the reincarnation of Judas Iscariot can give an upstanding British matron “something slightly Jewish about her profile”.

Weirdbuilding: There is a perfectly normal haunted house in the background of this story, which has almost nothing to do with the plot.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Perhaps Horace Acres was only “the victim of some miserable but temporary derangement”? No?

Ruthanna’s Commentary

This is an absolutely fascinating piece of horror drawn from two worldviews that don’t normally much move me: British Imperialism and Christianity. But like “Lazarus”, it builds on their uncanny implications rather than using them for comfort. That gives it more power than any would-be cosmic horror with lazily powerful crosses tacked on. Admittedly, Christianity is not normally big on reincarnation—but that was certainly part of 19th century British mysticism, so we won’t pry too closely into the precise relationship between punitive rebirth and purgatory.

Poor Bertha Acres! Gentle, kind, well-mannered, and caring – but unfortunately her soul hasn’t always been so, and hasn’t been forgiven. The idea of the inherent outcast is compelling of both sympathy and… other things. Appealing, perhaps, to those who feel rejected for no reason and wishes for worthily explanatory drama. Appealing more darkly to those who find themselves repelled by near-strangers, and would like to believe that their revulsion has logical justification. Benson is generally an empathetic writer, and seems to be reaching for the former rather than the latter—but there are problems.

Circling around to those problems the long way: the standout character in “The Outcast” is Charles. He’s totally not a fan AU of Mycroft Holmes—he just shares that character’s pleasure in exploration, complete lack of interest in practical application, and wealth that permits those eccentricities. (He is totally a fan AU of Mycroft Holmes.) He’s entertaining in both his speculations about consciousness and his lack of knowledge about golf. Never mind that he gets his kicks working with charlatans and conspiracy theorists —“You have to guess before you know.”

The Anglo-Israelites, as I mention above, were a real movement that has not entirely died off, but which was at its height during Benson’s lifetime. Fundamentally, it justified British imperialism with the claim that the Brits were descendants and heirs of the Lost Tribes of Israel. The thing about the Scone Stone is a serious part of their theory, thank you Charles for supporting that bit of nonsense. Anglo civilization is exemplified here by Madge resisting her intuitive revulsion and trying to treat Bertha like a human being. If that were the sort of thing that normally typified the British Empire, it would be a point in its favor.

There’s none of that morality in Charle’s speculation—his role here is to pull from pseudoscientific cruft the correct explanation for Bertha’s woes. And at that, he’s hasn’t even met her yet when he suggests the distress that might result from being Judas Iscariot in a past life.

Bertha proves that it really is distressing. What good does it do for humans to judge Bertha on her current life, if everything else rejects her? The only place she feels welcome is in a house haunted by the notable local religious traitor. But society will never accept her. Even those who try will find their souls sickening. The sea won’t suffer her to rest in it, and the kindly earth will not receive her.

Which is possibly where reincarnation comes in: if you can’t rest and wait for Judgment Day, you’ve gotta do something in the meantime.

Which leaves open the question: is this natural human response to a horrible crime, or divine punishment? Freya asks everything alive and dead to weep for Baldur; does the normally-forgiving Jesus ask everything to reject Judas? Would Bertha do better in some land with fewer Christians, or working in a prison with people who’ve screwed up in their current lives?

And is anyone else wandering around with these problems? Judas is not, except in some very specific Christian spiritual sense, the worst person to ever walk the face of the planet. Thus we come around to the possibility that when you shudder at someone on the street, there’s good moral reason behind it. And that makes for horror indeed.

Anne’s Commentary

In The Fiction Editor, the Novel, and the Novelist (1988), Thomas McCormack coins one of his many famous/infamous neologisms: Initium, “what the author had in mind when he began his novel.” McCormack didn’t mean what the author had in mind after planning out the novel (or other work), but what was the very first idea that popped into their brain. The kernel of inspiration, the spark that set off the creative conflagration, the one word or image that made the writer cry out like Jack Skellington, “What’s this!?”

What was Benson’s initium for “The Outcast,” I wonder? My top conjectures are:

- Hey, what if there was this person who couldn’t be buried? (After dying, that is.)

- Hey, what if you were a reincarnation of someone hated, or evil, or cursed, or all three?

The first initium could have led Benson to the second. Hey, but why wouldn’t a person be buriable? Were they so hated/evil/cursed that neither earth nor sea would abide them? What about fire, cremation? What about sky burial, or being eaten by any kind of animals, not just sacred vultures? What if even fungi or bacteria wouldn’t touch the corpse? You’d have to be pretty hated/evil/cursed for those to turn down a meal.

Which could have led Benson to ask: Who in history could be that hated/evil/cursed? There’s a species-embarrassing richness of candidates. Apparently, Benson had no particular religious convictions, but his father Edward White Benson was Anglican enough to become the Archbishop of Canterbury, while his brother Hugh converted to Roman Catholicism and became a priest. So E. F. definitely had a Christian background, even if he may have viewed it as does his iconic character Lucia:

“With regard to religion, finally, it may be briefly said that [Lucia] believed in God in much the same way as she believed in Australia. For she had no doubts whatever as to the existence of either; and she went to church on Sunday in much the same spirit as she would look at a kangaroo in the zoological gardens; for kangaroos came from Australia.”

The product of Christian culture, Benson undeniably was. “Outcast’s” characters also being such, it’s no surprise that Madge’s brother Charles, though he’s “never passed a moral judgment in his life,” hits on Judas Iscariot as the worst possible person to be reincarnated from. If Bertha stands in a line of people cursed to carry forward his soul, no wonder she’s at home in a house haunted by a brother’s betrayer. And of course, the sea won’t suffer her to rest, and the kindly earth won’t receive her. (As for Madge’s Biblical-sounding pronouncements, has anyone tracked them down to the Bible or elsewhere? I haven’t been able to.)

The bare-bones consensus about Judas Iscariot among historians is that he was one of Jesus’s twelve apostles, and that he betrayed Jesus to the Jerusalem authorities, crucifixion resulting. Certainly Judas is a central character in the Western cultural canon. As the subject of theological speculation, legend, and the arts, he’s a devilishly complex figure, whether or not he was ever possessed by Satan as some (looking at you, St. Luke) would have it. Conspiracy theories abound. Maybe Judas was a patriot disappointed that Jesus hadn’t driven the Romans from Judea. Maybe he was angry his apostolic teachings weren’t as popular as the other apostles’. In one verse (12:5), John writes how Judas protested that money spent on perfumes to anoint Jesus’s feet could have fed the poor. In the next (12:6), John lets the shade fly: “Judas did not say this because he cared about the poor, but because he was a thief. As keeper of the money bag, he used to take from what was put into it.” Would Judas throw Jesus under the chariot for 30 silver coins? Hell yeah.

One theological quandary centers on whether Judas is damned, and if so, why. If Judas was destined to betray Jesus, what role could free will have played in his actions? And if someone had to betray Jesus for him to save all our souls, shouldn’t that betrayer be forgiven? Some even suppose Jesus ordered Judas to betray him.

Whatever the theologians’ sincerity, some Christian authorities since the Middle Ages have personified the Jewish people in Judas Iscariot, making his betrayal one arrow in the antisemitic arsenal. Is Benson’s Charles Alington antisemitic because he so quickly settles on Judas as the Biggest Baddest Soul in the Reincarnation Lottery? I don’t think so. Not that it’s comfortable if he’s “merely” latching on to the obvious Big Bad in his cultural background.

Benson does allow Charles to discover “a medieval treatise on… reincarnation” that supports his Big Bad candidate. Quite the coincidence, but Tony admits Bertha’s tragedy contains many, if one’s to discount the supernatural.

At least the medieval treatise allows for Judas’s redemption. I hope Bertha Acres is the “cursed receptacle” that frees Judas through a purge by fire. Though wouldn’t people have tried cremation before now on unburiable corpses? Perhaps it’s Bertha’s trifecta of sea, then earth, then fire that does the trick.

To think it all happened in agreeable little Tarleton!

Next week, we open Part II of the nightmare with Chapters 36-37 of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary.