At a dinner party in Apple TV’s Severance, one character remarks, “Did you know that World War I used to be known as The Great War before World War II?” Everyone at the table goes “Whoaaaah.” The main character, Mark, replies, “Yeah, because before World War II happened, people didn’t know there would be another one.” Everyone at the table goes “Ooooooooh.” For context, these people are not “innies,” the newly born consciousnesses that exist while the characters are at work and which are dormant when they’re not at the office. They were either unsevered people or “outies,” whom we might expect to know about World War II. This is the state of intellectual life in Severance World.

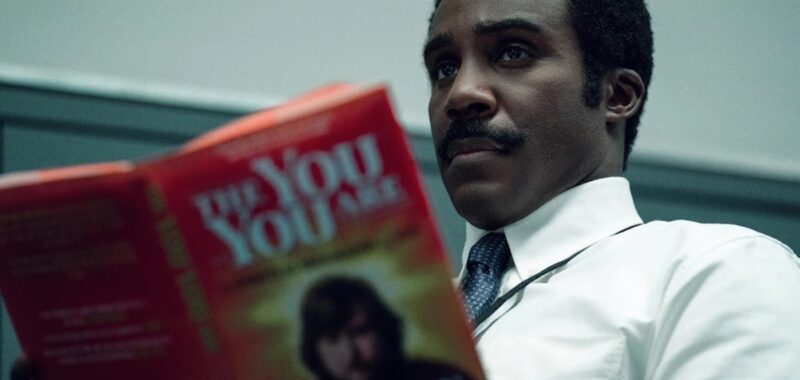

The best illustration of culture in the outie-verse would be the “literary” reading that takes place at the end of season one—Ricken Hale, an author, has a party at his house to celebrate the publication of his fifth book, The You You Are. The guests from his dinner party, along with a bunch of similar looking people, assemble to hear him read aloud: “It’s said that as a child, Wolfgang Mozart killed another boy by slamming his head in a piano. Don’t worry. My research for this book has proven the claim untrue. As your heart rate settles, though, consider the power an author, which we’ll refer to as Me, can hold over a reader, heretofore called You,” he reads.

While this is meant as a throwaway line that only Mark understands as gibberish, this opening rings true to Severance’s world: the narrative of the world you’re presented with does hold power over “You.” Since this show is about people whose bodies inhabit multiple selves, a title like The You You Are has a sneaky thematic significance. Mark’s innie is only told Lumon’s story: his outie is kind, according to Ms. Casey, and Kier Eagan is the “Chosen One,” according to a song we hear Ms. Cobel sing in season one. But we’ll come back to this question of identity later on. First: what might the innies talk about at a dinner party, if they were ever conscious during dinner?

Within the innie world, Lumon supplies the characters’ work selves with plenty of culture, but it’s in the form of a creepy cult of personality built around Lumon’s founder, Kier Eagan. The only museum we know of in the Severance world is the Perpetuity Wing at Lumon’s headquarters, an exhibit on the eight CEOs Lumon has had so far. The paintings hung around the Lumon offices are visually reminiscent of 19th and 20th century paintings; some neoclassical, some realist, and some vaguely Soviet / Surrealist, and they serve the same function as religious propaganda. All the innies are mandatory members of the Church of Kier, using their Lumon employee handbook as a kind of Bible.

It seems the characters in Severance haven’t just been severed from their work and private selves, they’ve been severed from the life of the mind as well. That probably suits the Lumon corporation just fine—if outies are sitting around talking about Ricken’s acrostic poem experience, they’re not mounting a meaningful opposition to Lumon’s agenda, and if the innies can only discuss the company handbook, they can’t imagine anything outside the company. As of season one, this strategy is working: it doesn’t seem to occur to most people in Severance World that they could oppose Lumon.

We might scoff at innies and outies alike in their artistic (and political) innocence, but real versions of these people walk among us: the tech bros advocating for generative AI to take over art are at the same level of cultural refinement as the characters in Severance. They’re creating apps to summarize books to people, tweeting from accounts with Greek statue profile pictures. Is this another article from a certified AI hater? Yes. But it’s also an article from a certified Severance enjoyer.

To promote the current season of Severance, Apple made Ricken’s book available for download; every single sentence is just like the excerpts we hear in the show. The ebook was also unintentionally immersive in its form: when I started reading The You You Are, I had only gotten through six pages before my Books app informed me my daily reading goal had been “achieved.” I have never set a reading “goal.” It felt like I had entered the Severance universe, to be congratulated for reading the introduction to a book.

The worst people in our culture are all about the hustle, and their reading is no exception. Book optimization seems to be the next frontier for Silicon Valley, from both the reading and writing sides. Amazon authors can churn out dozens of slop novels a month with GenAI, and tech bros can summarize Marcus Aurelius books into a paragraph or set of bullet points for consumption during a working lunch. They also listen to bro podcasts, which are just as bad.

GenAI would automate Lumon’s cultural mission, allowing humans to sever themselves from the production of art and culture. This would have the same effect as severing people from history; people would become more passive, less capable of taste. In fact, a study came out from Microsoft recently showing that the more a person uses AI tools, the worse they get at critical thinking. The atrophy described in this article seems a lot like the state of intellectual life in Severance World. People are left to exchange factoids without the ability to fact-check or contextualize, much less string two or more ideas together into a larger train of thought.

The throughline I see between Ricken’s aphoristic prose and a tech bro’s optimism about crypto is the refusal to think things through. Writing becomes a project of arranging words on the page until they look plausibly literary, a verbal Zen garden for empty-minded contemplation. Consider that some test subjects preferred AI writing to human writing, but only because it was written at a lower reading level. “Participants use variations of the phrase “doesn’t make sense” for human-authored poems more often than they do for AI-generated poems,” quoth the study. “In each of the 5 AI-generated poems… the subject of the poem is fairly obvious: the Plath-style poem is about sadness; the Whitman-style poem is about the beauty of nature… These poems rarely use complex metaphors… [The human-written poems] reward in-depth study and analysis, in a way that the AI-generated poetry may not.”

We might think, if a contingent of our society wants to voluntarily lobotomize themselves with GenAI, who are we to stand in their way? But this concerns more than just individuals—lower capacity for thought leads to a more docile population. The kind that allows their brains to be hacked by the company they work for, perhaps! It feels almost too on-the-nose to note that there’s a certain high profile tech company that literally makes microchips that can be implanted in people’s brains.

This isn’t just a vibes-level observation. We can see the underlying totalitarian culture of the Severance world by comparing it to the anti-intellectualism of our own.

Hannah Arendt wrote that incoherence was key to totalitarianism. If a government doesn’t hold itself to standards like “our policies have to make sense” or “we have to enforce our rules in logical ways,” then critics can’t effectively catch them in lies. If everything is a lie, then what’s different about any given lie? The government’s incoherence then prevents coherence on the part of the people. That’s why Ricken’s book is so nonsensical; it has no connections between its points. Once things are dumbed down to the point people need to be told a poem is about sadness, you can remove the final vestiges of meaning without protest.

This severance isn’t just one of meaning, but one of context. The compartmentalization of reality in Severance World prevents people from making connections in the present, regardless of their relationship to the past. Mark sees Ms. Cobel / Mrs. Selvig every day in season one, but he is unable to make the connection that she has two different identities because he has two different identities too. The difference between Mark and Cobelvig, a member of the ruling class, is that she can integrate her knowledge of Mark’s innie and his outie to form a bigger picture.

The theme of disconnection from context also shows up in the severance of privileged people from the consequences of their privilege. One of the most obvious Severance World examples would be the privilege an outie gets to not remember their work, and the consequence: an innie who is effectively enslaved. When Helly R. manages to contact her outie, an unusual occurrence, the outie sends her back the message that she (the outie) is a person, and Helly R., the innie, is not. The un-personing of the non-privileged is key to fascism, one more severing that must be completed by the state for the fascist project to be achieved. Residents of the fictional town of Kier are also severed from the outside world; we as viewers don’t know what, if any, consequences the outside world experiences to create the prosperity of this one area.

The most insidious part of the severance of meaning is the way it even works on people who are still trying to make the world make sense! Mark and his sister Devon are always put in situations where they’re nonplussed or frustrated at the obliviousness of their friends, but since they can’t get through the cultural shield of incoherence they have no choice but to tolerate the way things are. They’re the only people in each other’s lives who they can commiserate with about the people they know, and the viewer gets the distinct sense that this connection is what holds the two siblings’ sanity together through the events of the show. We see the same dynamic between Mark S. and Helly R. on the severed floor.

Connection in the sense of relationships is the other side of the coin from context. When people can form meaningful relationships, they can create a shared sense of reality and act. When people just exchange meaningless statements at a dinner party that does not include dinner, they’re atomized into a body politic that cannot perform its basic functions. The way the innies manage to connect on the severed floor, and the way Mark and Devon connect in the outside world, lays the groundwork for the characters to figure out Lumon’s larger plan—hopefully by helping the outies make contact with their innies, un-severing, or rather “reintegrating” their sense of meaning.

Connection and context can create the conditions for each other, but both are necessary for coordinated action. Mark and Ms. Casey manage to connect over the course of their wellness sessions, but without the context that Ms. Casey is really his wife, nothing can come of it. When Helly learns that she’s really Helena Eagan, she regains context, but without a way to connect with her outie, the two remain enemies.

And what happens when connection is restored through context, or context through connection? The moment the innies get access to Ricken’s book, it inflames them to revolt, even though Ricken’s book isn’t even good. The people don’t need a work on the level of Capital to question the government, just the tiniest sliver of a different perspective—and each other.

In a moment where many people are sitting around asking, “What can I do?” the Macrodata Refinement team can point us to the essential ingredients for resilience against severance. When we connect with each other, we form a social fabric that counteracts the effects of mental severance. When we learn history, we can rediscover the bonds we share with other humans.