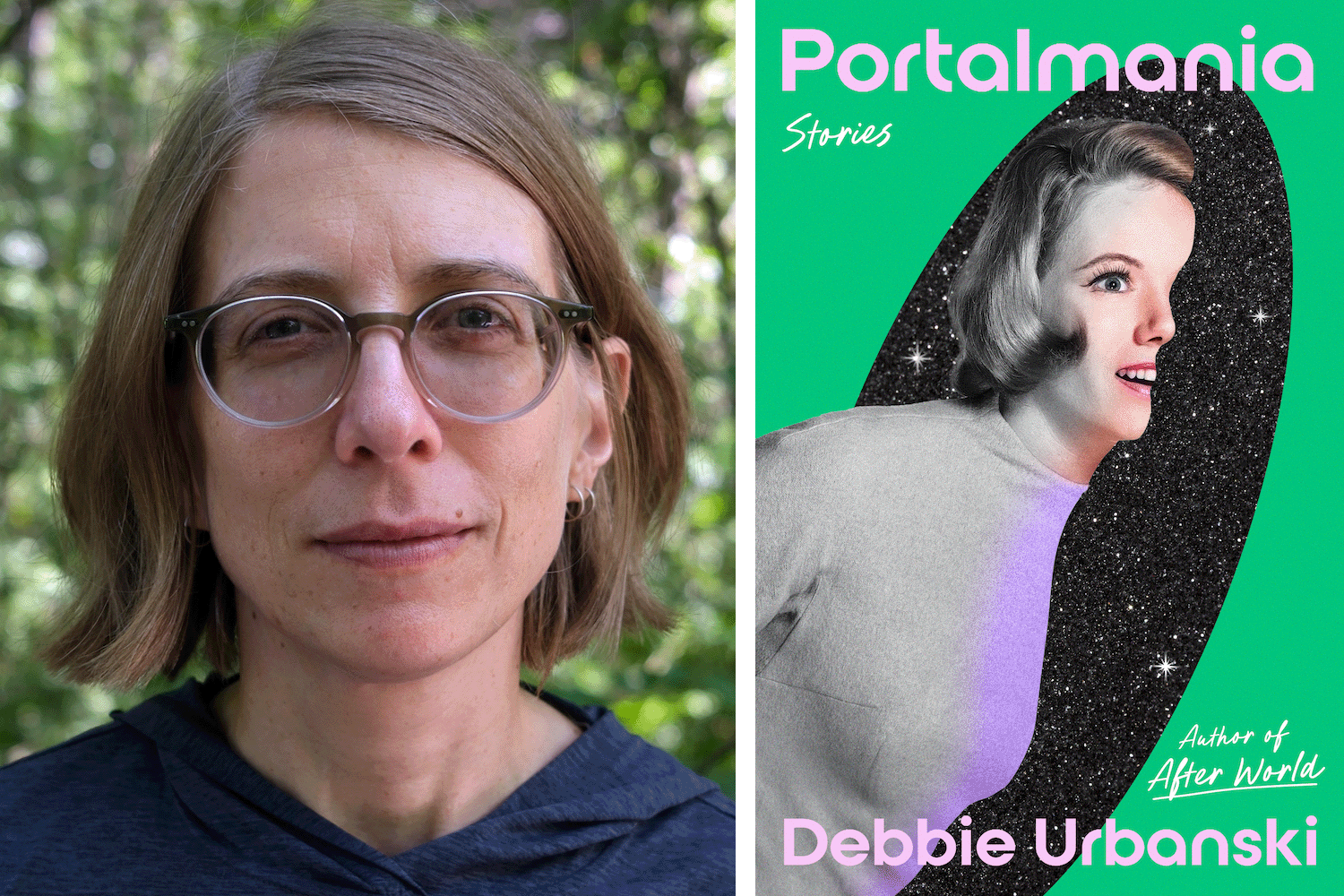

We’re thrilled to share the cover and preview an excerpt from Debbie Urbanski’s Portalmania, a genre-busting collection available May 13, 2025 from Simon & Schuster.

If you could go anywhere, where would you go? And what happens to the people you leave behind?

In Portalmania, Debbie Urbanski wields sci-fi, fantasy, horror, and realism to build a dark mirror that she holds up to the ordinary world. Within the sharply imagined landscape of this collection, portals appear in linen closets, planetary gateways materialize in boarding schools, monsters wait in bathroom vents, and transformations of women’s bodies are an everyday occurrence. Political division causes physical rifts that break apart the Earth’s crust. A son on another planet sends dispatches home to the mother who failed him, and a wife turns to the supernatural to escape her abusive marriage. Portals are not only doorways found in children’s classics, but separations, escapes, dead ends, desertions, and choices that will change these characters’ lives forever.

Against a fantastical backdrop, these stories dive bravely into the shadowy depths of betrayal, parenthood, revenge, murder, coercive sex, open marriages, asexuality, neurodiversity, and second chances. What if we’re not the ideal parents for our children? What if we’re not the ideal person to live our own life? Portalmania questions why we love as we do and asks if we have enough courage to reimagine desire.

Buy the Book

Portalmania

Debbie Urbanski is the author of the novel After World. Her stories and essays have been published widely in such places as The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy, Best American Experimental Writing, The Sun, Granta, Orion, and Junior Great Books. A recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, she can often be found hiking with her family in the hills south of Syracuse, New York. She is still looking for her portal.

A Few Personal Observations on Portals

The first portal that appeared in our town belonged to Mr. Hogan. It showed up in one of his bathrooms above the sink and proceeded to block a good deal of his vanity mirror, resulting in several shaving accidents. I don’t know why a portal appeared to him first. It’s not like he was the type to attract otherworldly things. Benny and I walked over to the Hogans’ house a few days after the rumors began. I carried a Ziploc baggie of homemade gingersnaps, intending to drop by for a chat. Before leaving the Hogan residence, I planned to ask to use their bathroom, the one with the portal in it. I assumed that having a portal would be a private matter, like having trouble with one’s digestion. They might not initiate the sharing of it. We would have brought along our son and daughter, only it was Saturday, so they had their own activities, basketball and figure skating respectively.

The Hogans resided on the other side of the park in an older and tree-lined neighborhood. Because of the crowd spilling across the sidewalk and into the street, I thought there must be some kind of festival that day, like the Hometown Homemade festival. Most people would find a portal’s appearance either suspect or ridiculous, I presumed, so they would stay away. There was no festival. The crowd consisted of some neighbors I recognized and others I didn’t know, attempting to form themselves into a resemblance of a line that led to the Hogans’ house. At the front of the line, in the driveway, sat Mrs. Hogan behind a folding table, collecting money. The various admission options were posted on a sign taped to the garage door. We could have chosen a day or weekly pass or a season pass that lasted through the end of October. I hadn’t brought my wallet with me. Neither had Benny. When we reached the fold.ing table, Mrs. Hogan said she’d vouch for us, and we could drop off the cash later that day. “Trust me, this is going to be worth the wait and the expense!” she promised as she wrote our receipt. By this point, Benny and I had eaten most of the gingersnaps. We offered the final cookie to Mrs. Hogan, who claimed she wasn’t hungry.

The Hogans’ bathroom, located on the first floor opposite the living room, was neither spacious nor modern. It was a half bath, a powder room I believe it’s called, and in desperate need of updating. At least they should have taken down the golden wallpaper. A lot of people were crammed inside that tiny room. The atmosphere felt festive and celebratory and also uncomfortable. Everyone was taking pictures, not only of the portal itself but also of the bathroom ceiling, and the contents of Mr. Hogan’s medicine cabinet, and the plunger, and the pair of identical toothbrushes set upon the vanity. Every item in that room radiated importance, including Mr. Hogan himself, who, dressed in an ill-fitted blazer and tie, knelt on the toilet, a few fresh scabs on his chin. Probably that blazer had been borrowed. Every few minutes, he recited a speech to whoever was in the room. “I think each of us might belong to a different world,” he said.

The portal itself looked spectacular hovering there above the sink. I still have a picture of it on my phone: a luminescent sheet that wavered as if caught in a crosswind. It smelled of mouth.wash and lavender. I stayed in the bathroom for as long as I could manage. Through Mr. Hogan’s portal, I saw a sky like ours, only the sky was filled impractically with many suns, so bright it was hard to look at. Mr. Hogan said he saw something very different. He wouldn’t tell us what he saw. At the close of his speech, he demonstrated how he could push his fingers through. Once, to much applause and hooting, he shoved through his entire arm. That must have hurt, judging from the way he cradled his elbow afterward, carefully kneading his skin. He promised us he had no plans to cross the threshold completely. “I don’t think I’d fit,” he said, laughing. He seemed to be suggesting the portal might not entirely want him. This turned out to be untrue, of course, as portals appear only to the people they want, but we didn’t know a lot of things about portals back then, and what we thought we knew was mostly wrong.

We left the Hogans’ bathroom after twelve minutes. A certain queasiness had come over me, a certain discomfort that cleared once we emerged from the house. “Lucky guy,” Benny said to me on the way home.

* * *

The following week, Ms. Bauer found a portal under her basement stairs. Her portal looked different from Mr. Hogan’s. This came as a surprise to a lot of people, myself included. Previously I assumed portals could only look one way, that they had to resemble a shining rectangle, like in the movies. Ms. Bauer’s portal was an odd shape with thirty-two sides—what is a shape like that even called?—and in addition it was short and squat. If you wanted to peer through it, you had to get down on your knees on the basement floor, which I don’t think had ever been swept.

Ms. Bauer charged an entrance fee as well. We brought the children and chose the family admission option. Despite her charging half as much as Mr. Hogan, there were only three others in line when we arrived. My children acted uninterested as we waited our turn. They said they had already seen numerous portals on their screens. “But this portal is real,” I told them. “Those other portals you saw might have looked real but they weren’t. They were made up for a movie.”

Billy said, “No, they were real.”

I said, “They weren’t real.”

Billy said, “They were real.”

I said, “Let’s go into the basement.”

In the basement, I made each child ask a question. “Can we touch it?” Billy asked, reaching out his arm. “No, you may not,” snapped Ms. Bauer. She had strung a nylon rope in front of her portal and ordered us to stay behind the rope. Jeanie asked if there was any milk to drink. To be honest, this was not a pleasant place to be. The basement was neither refinished nor upbeat. The portal, trapped under the stairs, resembled a dreary and many-sided rain cloud that produced its own atmosphere of dread. Benny was already on his knees in the center of the room. I made the children get down on the floor with me. “What do you see?” I asked them, struggling to breathe deeply.

“I see a little hill,” Jeanie said.

“Is this all it does?” Billy asked.

I stood up and dusted the filth from my knees.

“Too bad it’s not busier today,” I told Ms. Bauer.

“Oh, don’t you worry. They’ll come running later on,” she explained, so confident that her portal would remain special.

* * *

Our town’s third portal appeared to Mrs. Juliet Luna, who lived with her wife in a two-story bungalow across the street. They never shut their blinds for some reason so I always knew what they were up to. A week after Mr. Hogan’s portal appeared, I knew they had begun looking for portals of their own. Every evening I watched them. Mrs. Ada Luna carried a clipboard. Usually they searched the rooms together, but Mrs. Ada Luna was in the attic for some reason when Mrs. Juliet Luna peeked into the linen closet and found her portal, a circle the color of a sapphire and infused with light. She cried when she found it. For a long while, she, crying, stared at it pulsating beside the pile of folded towels, her face messed up with tears. Then she shut the closet door and went into the bathroom. I watched her splash water onto her face. She didn’t show the portal to the other Mrs. Luna until the follow.ing day.

After Mrs. Juliet Luna’s discovery, many people, including my children’s friends, began searching for their own portals.

“Are we getting portals too?” Jeanie asked me.

“I thought you weren’t interested in portals,” I reminded her.

“I like them now.”

“We aren’t getting a portal,” I said with such confidence. I didn’t know what I was talking about. Back then it seemed to me that portals appeared only to unhappy people. For example, it was a well-known fact that Mrs. Hogan desired to have sex while Mr. Hogan didn’t. She thought something was medically wrong with her husband. She kept dragging him to specialists and complaining in online forums about her “dead bedroom.” And Ms. Bauer had needed her stomach pumped twice in the emergency room. And Mrs. Juliet Luna could not find employment, having spent decades honing her skills as a switchboard operator. Nobody needed switchboard operators anymore. I see now how I was simplifying the situation: I wished to find a pattern, because I wished for the appearance of the portals to make a rational sense. What if portals weren’t rational? What if they were angry instead? Or vindictive? Or greedy? Or wrong? I believed my family was different from our unhappy neighbors. I loved my children. If children were loved as much as mine were, I believed they would want to stay where they are, rooted by my love. Likewise, I loved my husband. He was so familiar to me. We were experiencing our share of difficulties, sure, but such difficulties, I still believe, fall within the cyclical nature of a marriage. I have always considered familiarity to be the most stable form of love.

* * *

Portals turned up all over town. Many of the newer portals materialized to children. Though not only to children, and not everyone with a portal was unhappy. Honestly it was difficult to distinguish the rules, if there were any rules. One Wednesday, a portal appeared to the Riccis’ squinty-eyed newborn who could barely make out his mother’s face, let alone notice his own wispy portal stretching, like a web, across the corner of the hospital room. Nobody noticed the infant’s portal for hours in the chaos after birth. My neighbor Ms. Li, a night nurse, was the one to bring the baby’s portal to Mrs. Ricci’s attention. “Why on Earth would my baby need a portal? I think it’s actually my portal,” challenged the new mother. But there are certain feelings surrounding a portal, a certain force of feeling, which generally makes clear who the portal wants. When it isn’t yours, you experience a violence restlessly pushing against the inside of your chest. Maybe violence is too strong a word. But that’s what it felt like. A hard shove back. Eventually Mrs. Ricci asked that she and her child be moved to a different room. The baby cried all night and the night after that.

On Thursday, a dark portal appeared to Mr. Underwood, who is deaf in one ear and widowed.

My husband and I talked at night about the portals of other people. Here’s an observation: a person’s portal generally reflects some aspect of their personality. By studying people’s portals, it was like we were learning each other’s secrets or gaining confirmation of our suspicions. “Did you hear about Mrs. Sikora’s portal?” I asked Benny. Mrs. Sikora, a frequent visitor to the library where I worked, did not allow her children to read fairy tales or check out DVDs, even the educational ones. I found her overbearing and small-minded. The previous year, she campaigned to remove computers from the elementary school. “Her portal is the size of a quarter,” I told my husband. “I hear you can barely see anything through it, and what you can see looks like a dead end. Which is just about what I’d expect from her.” It seemed, at the time, like the portals were going to be okay, like the appearance of portals in our town would ultimately help us to understand each other. Also it gave Benny and me something to talk about in the evenings. Evidently your portal could appear anywhere, in the upper branches of a tree, or in the children’s section of a library beside the audio-books. But in all the excitement and newness, I think we forgot what portals actually are: a gateway to somewhere else. Meaning an exit. Do you get what I’m saying? It’s like we thought they were static works of art, these harmless and fascinating compositions that would not take people away.

Excerpted from Portalmania by Debbie Urbanski. Copyright © 2025. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.