Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover Sarah Monette’s “The Haunting of Dr. Claudius Winterson,” first published in Uncanny Magazine in January 2022. Spoilers ahead!

Kyle Murchison Booth (as you may remember) is the Senior Archivist in the Department of Rare Books at the Samuel Mather Parrington Museum. As an archivist, with a special interest in “occult esoterica,” he’s peerless; as a social butterfly, even by academic standards, he’s hopeless. He has just attended the public lecture of this year’s Henry T. Meadows Scholar, Dr. Claudius Winterson, about whom none of Booth’s colleagues have anything good to say. He has no intention of going to the reception, but his friend Dr. Claudia Coburn refuses to let him sneak home.

At the reception, Coburn abandons him to the garrulous Miss Parrington, a major donor he dares not offend. While she’s chatting, he notices a young boy in a black velveteen suit threading his way through the crowd. Who would bring a child to an event like this, Booth wonders. The boy seems to be following someone, but Booth can’t discern his “quarry”. Then the boy turns toward Booth, revealing that he has no face—from his hairline to his collar is “a gray blank, as if he were an unfinished drawing.”

Booth’s shocked recoil causes Miss Parrington to ask what’s wrong. He doesn’t bother pointing out the boy—he knows that no one else will see the apparition. Nor does Booth see it now, and he never does spot the person it was after.

Not that he knows what he could have done with that knowledge.

He escapes the reception without seeing the boy again. But come Monday there’s a faceless young girl in the hall outside his office. She’s waiting by Dr. Winterson’s door, “small and patient”. All of her is gray and black, with her fair hair nearly white. She looks as if “she had been clipped from a newspaper and her face smudged out—and then set free to find and follow… someone.” The girl doesn’t seem to notice Booth. He heads quickly in the opposite direction, wondering what Winterson could have done to attract such specters.

His plan is to do nothing about what he’s seen. It’s none of his business, and Winterson seems as hale and argumentative as ever. Booth can’t help but notice that two black-clad boys join the girl outside Winterson’s office, and that all three dog an oblivious Winterson, keeping ten feet behind him. In the coming days, though, Winterson’s behavior changes. His arguments grow louder and shorter, and he starts leaving the Museum before sunset. Booth still does nothing.

One afternoon, Winterson comes to Booth’s office. He understands Booth is the Museum’s occult expert, and after a brief hesitation he whispers, “You can see them, can’t you?” Booth tries hard to play puzzled, but Winterson’s not having it. The children, he insists. In the hall, waiting. Booth yields and asks who the children are. That’s not important, Winterson snaps, only how he can get rid of them.

What are the children anyway, ghosts, demons? Ghosts, Winterson concedes, but he dodges questions about why they’re haunting him. There was a hotel fire. The children didn’t get out. No, he’s not their father. He never even knew their names. The thing is, they’re getting closer. When he first saw them a week ago, they were ten feet away. Now they’re only six feet.

After revealing he saw one ghost at Winterson’s reception, Booth asks how long ago the fire was. Ten years, Winterson says. They may have been following Winterson since then, Booth implies, so what has changed so he sees them now?

Winterson says he doesn’t know. He’s lying, Booth senses, just as he’s lying when he says he has no idea why he’s the children’s target. At last, reluctantly, Winterson produces a yellowed newspaper clipping he received after the reception. Booth catches the headline THREE CHILDREN DIE IN HOTEL FIRE and beneath it, “I could do nothing,” said horror-stricken bystander. Before he can read further or study the photograph by the headline, the one with its subject neatly clipped out, Winterson repockets the clipping. No, he doesn’t know who sent it.

Somebody must think, Booth begins.

He knows what they think, Winterson shouts, but he couldn’t have saved them if he’d tried! Then, realizing what he’s admitted, he almost pleads: There was no way. Booth must know some way to keep the ghosts from getting closer to him.

Maybe there’s something in the stacks, Booth says, but it’s too late to look now. When Winterson says they could look tomorrow, he doesn’t argue. Winterson retreats to his office. Booth hurries to leave the Museum, but stops in the hall when he doesn’t see the ghost children. Moments later, Winterson screams in terror. A colleague rushes up and shames him into helping push open Winterson’s unlocked door. They discover that what’s blocking it is Winterson’s body. The colleague goes for help. Booth remains, staring at Winterson and wondering what the man could have done, and didn’t do, those ten years ago.

Looking up, he sees the children standing together in Winterson’s office, faceless heads turned toward him. The girl waves solemnly. The three ghosts vanish. The haunting of Claudius Winterson is finished.

To the corpse, Booth says that even if he’d searched the archives at once, he would have found only superstitions, anecdotes and outlandish theories. He couldn’t have helped.

And yet, the girl waved at Booth “as if to a friend. Or a co-conspirator.” And…Winterson was dead.

Weirdbuilding: Creepy children are never a good sign, whether or not they have faces.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Booth tries to suggest that Winterson is “deranged,” a “feeble” effort to put him off.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I love Kyle Murchison Booth. Our visits are too rare, and I always want to spend more time with him. The reverse, alas, is not true. Though he makes occasional exceptions, Booth would vastly prefer to be isolated in his office rather than face the horrors of social interaction.

So the political morass of a reception is his nightmare fuel. I can’t say I blame him. Particularly not at the sort of party people hold to honor those they hate, but who happen to have convenient connections and/or money. The Parrington is no more swimming in gold than any other private museum; they can hardly afford to neglect fashionable society.

Winterson, though, may be particularly unpleasant company. Booth avoids more people than he seeks out, but it takes someone special to earn the beneath-the-surface dislike of the Parrington’s more extroverted staff. For that matter, Booth doesn’t normally shy from providing supernatural aid—or rather, he usually provides it with minimal resistance despite his fears. The meek shall inherit, etc., as shall those who feel an obligation to do the right thing even when it will make them miserable. So why is Booth so particularly reluctant not only to help Winterson but to admit that he knows anything about his problem at all?

In other words, what’s the “nothing good” that Booth’s colleagues have to say about Winterson? Booth doesn’t openly acknowledge his refusal to tell us, suggesting something even more unspeakable than the true title of the Mortui Liber Magistri. Two possibilities suggest themselves. One is simply that the guy is an ass, and particularly nasty to women. Booth feels less protected by his manhood than others might, and word of bad enough behavior on the whisper network might raise both his fear and his anxious hatred.

The other, more or less opposite, possibility is that Winterson stands accused of the same affections that Booth represses—that Booth avoids him and fears working together because they have in common something that others condemn.

What we see of Winterson doesn’t suggest that he’s a particularly nice guy. But he doesn’t act worse than, say, Booth’s college crush.

We do know one terrible thing about Winterson: that ten years ago he failed to act, and three children died as a result. We don’t know how he failed. We don’t know how reasonable it is that he failed. We don’t know whether it was an active choice, or full cowardice, or loss of nerve at a key moment. We don’t know who it is that still blames him for their deaths—who knows his name even though he doesn’t know the children’s.

And so we don’t know how rational it is for either that unknown person to hold him responsible, or for Winterson himself to do the same. Faceless ghosts are not, after all, known for a nuanced sense of justice. But Winterson is far from the only person to carry such burdens. Booth, for example, has a number of haunting regrets, including the aforementioned crush.

And now he’s got a new one. About—and like—Winterson, he claims there’s nothing he could have done. But he didn’t have to wait for the man to approach him. He could have spoken to him, or even started preparatory research, when he saw the second child in the hall. He’s provided such warnings in the past, even when it’s made him miserable, and even when he expected to be a Cassandra.

But he waits. Everyone at the Parrington knows he’s the occult expert, and no one talks to him about it unless absolutely necessary—so Winterson must have been desperate enough to ask the questions that would get him directed to the specialist. Booth knows this, when Winterson comes to his door. And he still pretends ignorance. Even moreso than usual, he’s afraid to admit he’s seen anything. And Winterson, in turn, can only think of threats and begging to get his way.

Again, two possibilities. Two ways that Winterson might think they have something in common, that Booth would be afraid to have revealed. And again, we aren’t told. Like Winterson’s fate, the details are unspeakable.

Anne’s Commentary

We can add another color to the list of ominous hues that includes yellow (see Chambers “King” and Gilman’s “Wallpaper”), and fuchsia (which, according to film adaptations, is the closest we can get to Lovecraft’s “Color Out of Space,”) and red (sigil of the Death that visits Poe’s “Masque.”) Our new Tint of Terror is one so ubiquitous in weird fiction that we may only notice it when it’s cast like acidic ash into our eyes, and that is… gray. We’re constantly confronted with lowering gray skies and characters who, in the throes of death or illness or terror, have turned gray in their hair or complexions or both. Lately we’ve met an ashen-hued avatar of death in Jewett’s “Gray Man.” Now we meet three little gray ghosts.

Not that it’s uncommon for ghosts to be grayish, but Monette’s child-specters come in shades ranging from black to near-white for good reason: They’ve apparently been conjured from an old newspaper photograph.

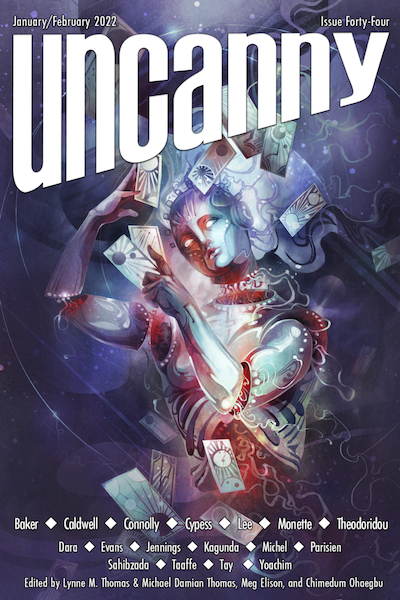

“Claudius Winterson” was published in Uncanny Magazine (Issue 44), along with Caroline M. Yoachim’s interview with the author, in which Monette says she’s a lover of ghost stories in general and M. R. James’s “Oh, Whistle and I’ll Come to You, My Lad” in particular. Monette goes deeper into her Jamesian influences in the introduction to The Bone Key, which collects ten of Booth’s “necromantic mysteries.” She “inhaled” James and Lovecraft in graduate school, savoring their “old school horror of insinuation and nuance.” Less satisfying were their “indifference to character development” and “dogged determination” to ignore sex and sexuality. In “Some Remarks on Ghost Stories,” James makes no bones about it:

“Reticence conduces to effect, blatancy ruins it, and there is much blatancy in a lot of recent stories. They drag in sex too, which is a fatal mistake; sex is tiresome enough in the novels; in a ghost story, or as the backbone of a ghost story, I have no patience with it.”

I guess James would’ve had negative patience for Booth’s debut story: “Bringing Helena Back.” Booth “emerged diffidently,” Monette writes, from the “weak, unstable narrator in thrall to his brilliant reckless friend” that was Lovecraft’s Randolph Carter, at least in his “Statement.” To this character dynamic, Monette added “an overt homoerotic element.” The “blatancy” of it all!

“Helena” couldn’t be Booth’s sole narrative, for Monette discovered in him “vast and complex” worlds. Besides, as she confides in the Uncanny interview and Bone Key introduction, KMB is her most “autobiographical” character. While this makes writing him “both nerve-wracking and cathartic,” if she’s doing it right, she “bleed[s] with him, and maybe the reader does, too.”

In today’s story, given Booth’s efforts to excuse his own failures to act, his conscience is doing plenty of retrospective bleeding. Whether Winterson deserves Booth’s self-flagellation is hard to determine. At the reception, Booth doesn’t see whom the faceless boy’s pursuing, so I think he’s justified in dismissing the matter as one of the psychic blips he’s subject to. Even if he saw the boy was after Winterson, what could he have done? Pointing out the phantom would have gotten him labeled as mad, since Winterson wouldn’t become aware of it for some time.

When the ghosts started congregating at Winterson’s door, Booth’s moral obligations remain hazy. After all, Booth’s the one whose nerves are suffering, not the oblivious Winterson. But as Winterson’s behavior deteriorates, Booth begins making excuses for his inaction: It’s still none of his business, and what advice could he offer anyhow?

Not much, unless he approached Winterson and found out what was going on while there remained time for intervention—a move too bold for reticent Booth. Speaking of reticence, remember how that’s the narrative strategy M. R. James recommends over blasted modern blatancy? Booth is constitutionally reserved. Winterson, normally loud and vigorous, is suspiciously reserved about the hotel fire. He doesn’t seek Booth’s help until he’s desperate about his pursuers.

Is it too late then? Booth’s intuition tells him Winterson could’ve done something to save the children, but didn’t. Ergo, the kids (and some magic-savvy survivor?) are out for revenge. Surely an occult expert like Booth could have tried generic methods to protect Winterson? I assume the ghosts feared such interventions, hence the ghost-girl’s nod to Booth as to a co-conspirator, one who aided the little avengers by inaction.

In the end, does literary reticence, the withholding of “blatant” details, strengthen or weaken “Claudius Winterson”? That depends on how tolerant readers are toward ambiguity, or if ambiguity-intolerant, how willing readers are to flesh out the tale for themselves.

If Monette’s point is to make Booth “bleed,” and maybe the right reader to “bleed” with him, it’s better if Booth never learns how much Winterson deserved his end. If Winterson was a monster either of malice or cowardice, Booth could feel exonerated in having ignored his plight. He wouldn’t have to bleed at all, or very little. If Winterson, overall jerk though he is, really couldn’t have saved the children, Booth could in unavailing guilt bleed too much.

For this kind of ghost story, we readers want to bleed with the narrator just enough, especially when he’s a socially awkward but lovable geek like KMB.

Next week, we continue to figure out how badly Louis and Jud screwed up in Chapters 30-32 of Pet Sematary.