James Murdoch was seated at a conference table in a Manhattan law office in March 2024 when he realized he was witnessing the final dissolution of his family.

Three months earlier, his father, Rupert, had told James and his sisters that he was rewriting the family trust to grant his elder son, Lachlan, full control of the Murdoch empire after his death, rather than splitting it equally among his four oldest children. The amendment was part of a secret plan that the patriarch’s allies had code-named “Project Family Harmony.”

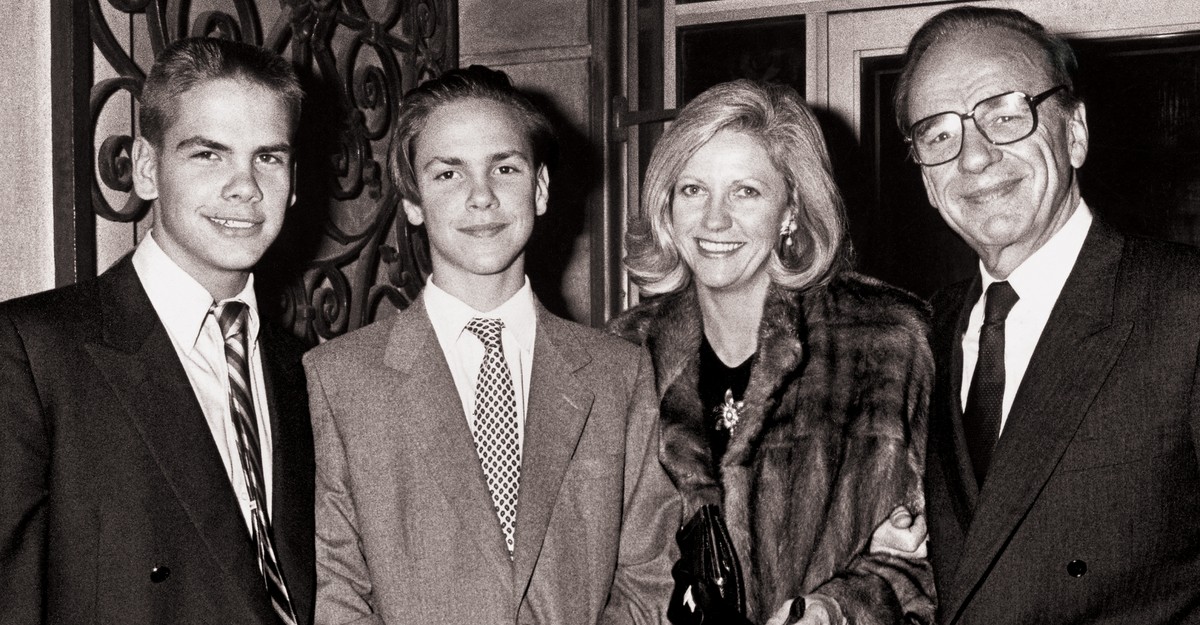

Rupert’s shocking decision was the climax of a succession battle that had pitted James and Lachlan, born just 15 months apart, against each other essentially their entire lives. (Their older sisters, Prudence and Elisabeth, had never been serious contenders to run the business: “He is a misogynist,” James said of his father.)

Rupert believed that he had no choice but to take aggressive action. He was 92 years old, and was certain that James was plotting with his sisters to seize control of the family’s companies as soon as he died, after which they would defang his conservative media empire and destroy his life’s work.

He was right that his younger son did not share his vision for the family business. James had come to see Fox News as a blight on his family’s name and a menace to American democracy. He believed that drastic changes were needed to save the companies from the consequences of his father’s reckless mismanagement. (“If lying to your audience is how you juice ratings,” he would tell me, “a good culture wouldn’t do that.”) Determined to retain a voice in the business, James and his older sisters had moved to block Rupert from changing the trust.

The legal drama was set to play out far from public view, in a Reno probate court—Nevada is known for its flexible estate laws—but it had global significance: The trial would determine who controlled the most powerful conservative media force in the world, one that had toppled governments and delivered Donald Trump to the White House. For the Murdochs, the stakes were also intensely personal. Depositions and discovery were surfacing years of painful secrets—intra-family scheming and manipulation, lies and leaking and devious betrayals. James and Rupert had barely spoken in years.

In the communications that emerged during the discovery process, James had learned how his father talked about him to the rest of the family—how calculating and manipulative he could be. When a packet of documents that James’s lawyer had requested arrived from Rupert, it came with a handwritten note: Dear James, Still time to talk? Love, Dad. P.S.: Love to see my grandchildren one day. James, who could not remember the last time Rupert had taken an interest in his grandchildren, didn’t bother to reply.

Now, at the Manhattan law office, James sat across the table from his father and prepared to be deposed. For nearly five hours, Rupert’s attorney asked James a series of withering questions.

Have you ever done anything successful on your own?

Why were you too busy to say “Happy birthday” to your father when he turned 90?

Does it strike you that, in your account, everything that goes wrong is always somebody else’s fault?

At one point, the attorney referred to James and his sisters as “white, privileged, multibillionaire trust-fund babies.” At another, he read an unsourced passage from a book about the Murdochs to suggest that James was a conniving saboteur.

James did his best to concentrate, but he couldn’t help stealing glances at his father. Rupert sat slouched and silent throughout the deposition, staring inscrutably at his younger son. Every so often, though, he would pick up his phone and type. Finally, James realized why. “He was texting the lawyer questions to ask,” James told me. “How fucking twisted is that?”

When the session ended, Rupert left the conference room without saying a word.

James Murdoch likes to think of himself as a student of dynastic dysfunction. He quotes Shakespeare and cites Roman imperial history in casual conversation. He is not sure he agrees with Tolstoy’s dictum—“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Because when he surveys the literature on families wrecked by wealth and power, he mostly sees the same sad patterns in endless repetition.

The contours of his own family’s story are familiar to the point of cliché—the legacy-obsessed patriarch slipping into senescence and paranoia, the courtiers whispering in his ear, the siblings squabbling over their portion of the kingdom. “It’s all been written down many, many times,” he said. “The real tragedy is that no one in my family doing this bothered to pay attention.”

There had always been rumors about James—his more liberal politics, his rifts with Rupert—but over two decades as an executive at News Corp and Fox, he’d played the good soldier and loyal son. He’d even been groomed at various points to be his father’s successor. Then, in 2020, he abruptly resigned from News Corp’s board of directors in a short letter citing “disagreements over certain editorial content” and “other strategic decisions.” James had never fully explained what led to this decision, and when I approached him in early 2024, I hoped he might be ready to elaborate.

I didn’t yet know that the Murdochs were in the midst of a private meltdown over the family trust. But the trial, I would learn, was really the culmination of a decades-long story—one that James decided he was finally ready to tell.

Over the next year, he and his wife, Kathryn, told me about the mind games at a Murdoch family-counseling retreat, and all the ways that Rupert had devised to pit his sons against each other. They detailed the cynical deliberations that had led the family’s news outlets to support Brexit and Trump, and the machinations that various family members had undertaken to get one another fired or subpoenaed or humiliated in the press.

Some of these stories felt strangely familiar, having appeared in slightly altered forms on Succession, the HBO drama about a fictionalized family very much resembling the Murdochs. James had never watched the series; he’d tried the first episode, but found it too painful. But other members of the Murdoch clan were obsessed with the show; certain scenes and storylines seemed uncannily true to life. Throughout my reporting, I heard constant speculation about which family members might secretly have leaked to the show’s writers. James and Kathryn, I was told, thought his sister Liz was responsible. Liz swore she wasn’t, though for a while she was convinced that her ex-husband was talking with the writers—and in fact she later learned that he’d repeatedly offered his services, but the showrunner, Jesse Armstrong, had declined. Armstrong told me that he and his writers simply drew on press reports. “I think there’s a bit of psychodrama around this sort of thing,” he told me.

Airing the dirty laundry didn’t come naturally to James. In our conversations, he vacillated between seething anger toward his father and an odd kind of protectiveness. Trim and neatly dressed, he spoke in an even, British-inflected staccato that seemed to belie a subcutaneous anxiety. Sometimes, when I would ask him about a particularly painful episode with his father, he would find that the dishes suddenly needed clearing.

Kathryn often took on the role of taskmaster. In one meeting, James began our interview by speaking rapidly for 11 straight minutes about the adaptive cruise control on his Tesla, and the new venture he was launching with Art Basel, and his daughter’s summer internship working with giraffe conservationists in Zimbabwe. Finally, Kathryn interjected. “Sweetheart,” she said firmly. “I think you need to take a breath, take a sip of water, and maybe we should just talk about what we want to talk about.”

James had long ago internalized the edict that you never talk to reporters about the family. This was an inviolable rule of Rupert’s—one of the first things Kathryn had learned when she and James started dating. James hated the books and articles written by professional Murdoch chroniclers, which he mockingly referred to as “the canon.” It wasn’t until his father’s texts and emails came out in the trust litigation that James realized just how many insidious stories over the years—the ones that portrayed Kathryn as a meddling “former model” and James as a liberal dilettante—had been planted by Rupert’s camp. The revelation was liberating.

The couple’s motives in talking to me were surely mixed. Sometimes, they seemed fueled by raw anger at what they see as Rupert’s betrayal. Other times, they seemed preoccupied with reputation management—eager to present themselves as evolved, socially conscious billionaires, and distance themselves from certain unfortunate associations with the Murdoch name. (Rupert and Lachlan declined to be interviewed for this story, but a spokesperson objected to what he called a “litany of falsehoods,” noting that they came “from someone who no longer works for the companies but still benefits from them financially.”)

James also seemed compelled, in part, by a desire to add his chapter to the literature of family dysfunction, in hopes that some future family might take the lessons more seriously than his own had. During our first meeting, he told me about a document that one of his father’s lawyers had written, which included a quote from King Lear: “How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless child.”

James and Kathryn found it darkly amusing. Did Rupert and his lawyers not realize that the famous line uttered by the mad king is aimed at Cordelia, who turns out to be Lear’s only honest daughter?

“The whole point is that the crazy old man doesn’t know that Cordelia is telling him the truth,” Kathryn told me. Her husband studied a spot on the table in front of him.

Rupert’s media empire has its own mythology, one that every Murdoch learns at an early age. The story begins during World War I, when a young reporter named Keith Arthur Murdoch visits Australian soldiers fighting in Gallipoli. There, Keith learns that the campaign has been a secret disaster. His countrymen are dying by the thousands, serving as cannon fodder for the British military. Press reports are supposed to be submitted to military censors, but Keith—exhibiting a rebellious streak and a nose for a great story—smuggles out news of the slaughter in an 8,000-word letter. The dispatch circulates widely in Australia, sparking public outrage, changing the course of the Gallipoli campaign, and turning Keith into a national hero. When he dies, in 1952, he leaves a newspaper in the coastal city of Adelaide to his 21-year-old son, Rupert, hoping to plant a dynasty.

Rupert graduates from Oxford and returns to Australia in a hurry to turn his inheritance into an empire. He conquers the country’s media landscape in a reckless scramble, buying one newspaper and leveraging it to finance the debt for the next. He gobbles up TV stations too. Murdoch outlets become known for an irresistible mix of sports, scandal, and populist outrage; some observers will later call him the inventor of the modern tabloid. By the time he’s 40, he is the most powerful media figure in Australia, eventually controlling two-thirds of the country’s newspaper market.

Rupert discovers that one of the great pleasures of being a press baron is wielding political power. After he arrives on Fleet Street, in the late ’60s, he buys a pair of popular British papers and uses them to successfully campaign for Margaret Thatcher, who later clears a regulatory path for Rupert to expand his British TV holdings. When he turns his attention to the U.S., he uses his acquisition of the New York Post to befriend an up-and-coming GOP operative running Ronald Reagan’s New York campaign. He works with Roger Stone to shape the candidate’s image, helping Reagan carry the state.

In the New York media world, Rupert’s conservative politics are held in suspicion, and his rapid pace of acquisitions—which include New York magazine and The Village Voice—is alarming. He appears on the cover of Time in 1977, his head pasted onto the body of King Kong, above a screaming tabloid-style headline: EXTRA!!! AUSSIE PRESS LORD TERRIFIES GOTHAM. But Rupert doesn’t care about popularity; he takes a certain arch delight in his nefarious reputation.

Once Reagan is in office, his administration waives a rule against owning TV stations and newspapers in the same market, allowing Rupert to launch his own TV network in America. Analysts call him foolish for trying to take on CBS, NBC, and ABC. But Rupert fills Fox’s prime-time lineup with provocations—sitcoms about dysfunctional families (The Simpsons, Married … With Children); pulpy crime shows (Cops, America’s Most Wanted )—and the network is an unexpected hit. He defies expectations again when he decides to challenge CNN’s cable dominance by launching a right-wing news channel.

Amid all the empire building that follows—the movie studio, The Wall Street Journal, HarperCollins, the push into Asia—Rupert insists on treating News Corp like a family business, drawing his children into his professional world at every opportunity. At breakfast, he spreads the day’s newspapers across the table, and gives his children a master class for budding media moguls. Family dinners feature visits from politicians and dignitaries. He takes his children on tours of printing presses, and gives them internships at his newspapers.

This is his animating motivation, he insists, his conglomerate’s entire reason for being. He loves his children, and he wants to leave them an inheritance that means something, just as his father did for him. “I don’t know any son of any prominent media family who hasn’t wanted to follow in the footsteps of his forebears,” he says. “It’s just too great a life.”

But there is one episode that often gets left out of the official mythology. In the early ’90s, News Corp is in trouble, the result of a debt crisis brought on by Rupert’s relentless expansion. It has lost the confidence of the markets, its share price is depressed, and it is nearing bankruptcy. Rupert sees an opportunity in the crisis.

Before dying, it turns out, his father placed his newspaper holdings in a trust and divided control equally among his wife and four children. Although Rupert has run the company all these years, he’s never truly owned it. Now, he decides, it’s time for that to change.

Taking advantage of the low stock price, he informs his mother and siblings that he is ready to buy them out: He makes clear that he is not interested in negotiating. When the family meets to discuss the matter, his biographer Michael Wolff will later report, Rupert’s mother “buries her head in her arms on the boardroom table.”

In Rupert’s conception of the family empire, the empire always takes precedence over the family.

The Upper East Side penthouse where James spent his childhood had a private elevator entrance and a butler named George and panoramic views of Central Park. But kids want their fathers, and James’s was busy. “Is Daddy going deaf?” he once asked his mother, Anna, when he was young. “No,” she replied, “he’s just not listening.” Those storied bonding moments at the breakfast table were less rituals than special occasions, as far as James recalls. His parents moved to Los Angeles when he was around 16 and left James behind in Manhattan to attend the elite Horace Mann School. He would go long stretches without seeing them. When Rupert did come to town, striding into the penthouse in his double-breasted suits, talking about important things with a gaggle of employees, it felt almost like spotting a celebrity.

In the roles assigned to the Murdoch children when they were young, Prue was the peacemaking older sister from Rupert’s first marriage; Liz, the temperamental artist. The two boys were treated almost like twins—rivals in the unspoken competition for Rupert’s approval. Lachlan was the golden boy, the elder son and heir apparent, rugged and charismatic and self-consciously emulative of his father. James, the intense, cerebral kid who bleached his hair and pierced his ears and provoked his father at the dinner table with contrarian questions, was typecast as the rebel.

James bristles at the caricature now, but he admits that he was “not an easy son.” He got into trouble at school, and demonstrated a lack of interest in his father’s work that could reasonably be construed as disdain. When, at 14, James interned at Rupert’s Australian newspapers, he fell asleep during a press conference, and a photo of the snoozing scion wound up in the rival Sydney Morning Herald.

As a teenager, James spent summers at an archaeological site in Italy, digging holes alongside a bohemian collection of grad students, artists, and antiquities scholars. When they tried to provoke him with questions about politics, he responded simply, “I’m not my father.” He loved the work, and the freedom that came with it. Richard Hodges, who oversaw the excavation, thought James would make a worthy protégé, but he knew it wouldn’t happen. “His father wouldn’t have allowed him to do that,” Hodges told me.

Still, the fact that Lachlan was the obvious successor gave James room to shape his own identity in those years. After graduating from high school in 1991, he enrolled at Harvard, where he got a tattoo, grew a beard, and began drawing a satiric comic strip for The Lampoon called “Albrecht the Atypical Hun,” about a kindly, poetry-loving World War I–era German who feels excluded because he doesn’t enjoy war crimes. James dropped out his senior year and moved to New York to start a hip-hop label with his friends. The offices for Rawkus Records featured a poster of Chairman Mao.

He met Kathryn Hufschmid in 1997, when he was 24, aboard a charter flight to Fiji, where he, his brother, and an assortment of models, surfers, and Australian bodybuilders planned to spend a long weekend on a yacht. It wasn’t really James’s scene, but he was happy to find himself sitting next to a quiet, pretty blonde who shared his love of the Salman Rushdie novel Midnight’s Children. “We hardly saw them the whole weekend,” recalls Joe Cross, a friend who was on the trip. “They’d surface for meals.”

Kathryn was living in Australia at the time, and James was in New York, so for their second date, they met halfway, in Hawaii. For their third, James invited Kathryn to meet his family on his father’s 158-foot superyacht, Morning Glory, off the coast of Australia. They were already talking seriously about their future, and the trip was a chance for Kathryn to see what she’d be getting into.

The experience was enlightening. She caught Rupert cheating at Monopoly (he just smirked and shrugged), and observed constant sniping—at one point, Anna got up and left a family dinner in tears. Lachlan had brought along his latest girlfriend. When they got into an argument, Kathryn recalled, Lachlan shaved his head, jumped off the boat, and swam to shore. “He has a weird, dramatic side,” James told me. (A spokesperson for Lachlan denied James’s version of events.)

Kathryn had grown up the only child of a single mother in Oregon, and left home at 15 to pursue modeling. She wasn’t scared off by this big, noisy, disputatious family—the prospect of having a family at all appealed to her. And she left a good impression: After the trip, Rupert urged James to propose as quickly as possible. They were married at a small ceremony in Connecticut, where James read Pablo Neruda and Kathryn read James Joyce.

“She was very fond of Rupert, and she’s a very loyal person,” Chloe Hooper, a longtime friend of the couple’s, told me. “I don’t think she ever anticipated that 25 years later, she would be in this ideological knife fight with them.”

On June 25, 1999, guests boarded the Morning Glory, now anchored in New York Harbor, to watch Rupert Murdoch marry Wendi Deng.

Rupert had finalized his divorce from Anna, his wife of nearly 32 years, just 17 days earlier, and both James and Lachlan objected to their father’s new marriage. The brothers believed that Deng, an executive at a News Corp subsidiary in Hong Kong, couldn’t be trusted, and suspected that she might even have ties to Chinese intelligence. (Deng has denied this, but James’s suspicion never died. More than two decades later, Kathryn would joke that Deng used “CCP-issued burner phones” to evade a subpoena in the trust litigation.)

It was a time of broad upheaval for the family. Liz had split from her husband and taken up with Matthew Freud—an intense, unnervingly slick PR executive from London (and a great-grandson of Sigmund). The Murdochs, always skeptical of interlopers, were especially wary of Freud, with his constant flaunting of social connections and his gleeful loutishness. The first time Kathryn met him, she recalls, he started the conversation by trying to convince her that it was morally defensible for a man to cheat on his pregnant wife.

At the wedding, Rupert gave a long, glowing speech about his new wife, while a barefoot Deng looked on adoringly. James and Kathryn parked themselves by a bucket of caviar and got drunk.

James had joined the family business a few years earlier, after Rupert bought Rawkus Records and folded it into News Corp’s fledgling music and new-media group. James’s title, head of “digital publishing,” was not an especially exalted one at a dead-tree media company. Lachlan was the one on the succession track—immersing himself in the tabloid business so beloved by his father and eventually apprenticing with the chief operating officer.

Before long, the New York City headquarters started to feel a bit cramped for both of the boss’s sons. At board meetings, James—ferociously analytical and eager to one-up his older brother—would freely challenge Lachlan, picking apart his logic and questioning his ideas. Lachlan, for all his easygoing confidence, was not as articulate as James—he had struggled with dyslexia and spent time in speech therapy as a kid—and sometimes grew flustered. The feuding was awkward for others in the room, but Rupert rarely stepped in to break them up.

In 2000, Rupert decided to give James a new assignment that would take him to Hong Kong. James had recently worked with his mother to impose some semblance of peace on the family. During the divorce, Anna had asked her younger son to meet with her. She told him she was prepared to give up half of the money to which she was entitled in exchange for alterations to the family trust. Anna had seen the way Rupert played the kids off one another, how he picked favorites, how their lives risked becoming consumed with a never-ending quest for the crown. What she wanted was an arrangement that would split the family fortune—and the empire—evenly among the four children once Rupert was gone.

With James acting as mediator, his parents reached an agreement. The trust would now give Rupert four votes and each of his four children one. When he died, his votes would disappear and control of the company would be split among Prue, Liz, Lachlan, and James.

“The idea,” James would later recall ruefully, “was that it would incentivize us to cooperate.”

In Hong Kong, James found that he thrived working 8,000 miles away from his father. He began repeating, almost like a mantra, a Chinese proverb: “The mountains are high and the emperor is far away.”

He had been sent to turn around Star, an Asian satellite-TV company that had lost $200 million since News Corp bought it, in 1993, and was mired in mismanagement. The job had been presented as a big opportunity, but it looked to some like a suicide mission for a green 27-year-old.

James’s first move was to pivot Star’s growth strategy from Hong Kong to India. He ordered an overhaul of Star’s Indian programming, commissioning mass-market shows in regional languages. After Star debuted an Indian version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, James built on the prime-time success by ordering a series of splashy Hindi-language dramas. Two years after he arrived at Star, the company turned a profit.

James’s success in Asia came as something of a surprise back at News Corp headquarters, people familiar with the company told me. “I have to be honest,” James recalled one board member telling him, “I didn’t think you had it in you.”

A promotion came in 2003, when James was named CEO of British Sky Broadcasting, a large satellite-TV company in which News Corp owned a 39 percent stake. His arrival in London was noisy and unwelcome. Rupert, whose down-market tabloids had earned him the nickname the Dirty Digger, was a villainous figure in Britain, and the appointment of his son to run a major British broadcaster prompted howls of nepotism and a sharp backlash in the market. On the day James made his first major presentation to investors, Sky’s share price dropped nearly 20 percent.

Sky was profitable, but stagnant. Among Brits, it was widely seen as a price-gouging service that bought Premier League soccer rights and ransomed them to resentful subscribers. Its internal culture was macho and belligerent. The predominant mentality, James recalled, was “Everybody hates us and we don’t care.”

Early on, James laid out his vision for a new, respectable Sky. The company was going to have a set of “values,” he told executives, and would adopt the best practices of a modern workplace. “All these grumpy, old English guys were looking around like, ‘What the fuck is this guy talking about?’ ” James told me.

He pushed out Sky’s CFO and several other executives. After hearing that an employee had gotten drunk at a Royal Television Society banquet and thrown a dinner roll at the former director-general of the BBC, James ordered a manager to sack him. James told me that when the manager resisted, he had to explain why “being a dick in public when you’re an ambassador for the company” was a fireable offense.

Under James’s leadership, Sky’s brand image improved and subscriber numbers grew. “He took what was this Aussie-inflected cowboy operation, and turned it into a respected, high-growth company,” Matthew Anderson, an executive who worked with James at Sky, told me.

But James could feel Rupert’s ambivalence. He had succeeded in large part by rejecting the corporate ethos cultivated by his father. Rupert had a well-known management modus operandi: Hire aggressive executives, give them their own fiefdoms, and let them run wild. It was central to the Murdoch mythology—the empire built on instinct, run by a shrewd band of self-styled pirates and gamblers.

In London and New York, James told me, the pattern was the same: Nobody seemed to listen to the in-house lawyers if they could help it, and human resources was an afterthought at best. “When I’d say things like ‘compliance,’ they’d be like, ‘Oh my God, he uses business-school speak!’ ” James recalled. “And it’s like, ‘No, it’s the English language, and it’s kind of an important idea.’ ”

Rupert, for his part, seemed to resent his son for what he saw as a preoccupation with respectability, according to former News Corp employees. His misgivings were exacerbated by his apparent belief that Kathryn had indoctrinated James in fashionable left-of-center politics. The caricature periodically popped up in press coverage of the family: the witchy, liberal daughter-in-law casting a spell on Rupert’s impressionable son.

It was true that Kathryn was becoming more political. An awakening came, of all places, at a News Corp retreat in Pebble Beach, California, where she listened to Al Gore deliver his famous presentation on climate change. Soon after that, Kathryn went to work for the Clinton Climate Initiative. She also became more outspoken while sparring with her in-laws.

Once, during an argument over gay marriage, Rupert asserted that allowing same-sex couples to wed would be an affront to the institution.

Some people would say the same thing about divorce, Kathryn told her father-in-law. Rupert was then on his third wife.

Still, Rupert couldn’t afford to push away his younger son. Lachlan had left the company in 2005 after a series of confrontations with his father’s lieutenants in New York. The final indignity came when Lachlan, who was in charge of Fox’s TV stations, delayed green-lighting a police series developed by Roger Ailes, the CEO of Fox News. Ailes went over Lachlan’s head to Rupert, who reportedly told him, “Do the show. Don’t listen to Lachlan.” After years of being undermined by his father, who seemed conspicuously uneager to retire, Lachlan had had enough. He resigned and moved his family back to Australia.

With Lachlan effectively taking himself out of the running, James was the new successor in training. In 2007, he resigned his post at Sky to take a major promotion running all of News Corp’s operations in Asia and Europe. James’s domain would be larger than ever.

The James Murdoch who moved into News Corp’s corner office in London was all but unrecognizable to many who had known him earlier in life. He’d always been a “bundle of pent-up energy,” as one former employee put it to me, but now he was brash and cocksure. He charged into a rival newspaper’s office to castigate the editor for running an ad campaign critical of his family. He insinuated himself with major shareholders and dined privately with David Cameron. To some observers, he looked like a boy trying on his father’s sport coat, but James clearly felt like he was on a hot streak.

He assembled a team of loyal deputies—young men in dark suits and open collars who were similarly fluent in M.B.A. jargon—and launched an ambitious bid to acquire the part of Sky that News Corp didn’t already own. If completed, this would be the largest acquisition in the company’s history. By all appearances, James was establishing a rival power center on his side of the Atlantic—and he could sense that his growing confidence agitated his father.

In the 2008 biography for which he interviewed Rupert and his children at length, Michael Wolff noted an odd dynamic forming between James and Rupert around this time. James seemed to be deliberately cultivating a public persona modeled after his father’s—but rather than bringing the two men closer, the performance appeared to threaten Rupert. “His father is obviously proud,” Wolff wrote, “even perhaps slightly afraid of him.”

Then one day in 2010, Rupert did something out of character: He invited his adult children to a family-counseling retreat in Australia. He explained that he’d hired a therapist who specialized in families like theirs, and said he believed the guy could help them.

The retreat was held at the Murdoch family’s ancestral ranch in Cavan Station, a 25,000-acre farm a few hundred miles from Sydney where Merino sheep roam the plains and kangaroos have to be culled. The purpose was not ostensibly to discuss succession planning, James recalled, but rather how they would “behave with each other.” (“Was this more business or personal?” I asked. “There’s no difference in this family,” he said.)

Lately, Rupert had been talking with Liz about acquiring her production company, Shine Group. James didn’t think his sister should sell—she’d turned Shine, which produced megahits such as The Biggest Loser and MasterChef, into a success all by herself. Why let their father get his claws in it?

“My father was always trying to pull everyone into the company so that he could manipulate them against each other,” James told me.

The therapist began by sitting down with each Murdoch individually to get their view of what was wrong with the family. James, skeptical of the exercise, remembers telling him, “There’s some stuff you don’t need to pick at—nothing good is going to come of it.”

Sure enough, when the therapist convened the family, the session devolved into posturing, gaslighting, and recriminations. Everybody was spinning stories to garner strategic sympathy and advance their own agenda, James and Kathryn told me. “I think that the shrink was outmatched,” Kathryn said.

“It was a car crash,” James said. “Everyone was more alienated from each other at the end.”

Not long after that weekend, a mention of the Murdochs’ family therapy made it into Vanity Fair. Whoever leaked the story described a loving, supportive experience: James’s siblings advocating for their little brother, eager to help him strengthen his relationship with their father so that he’d be ready to take over the business one day. When I read this account to James, he scoffed.

The family-trust litigation had recently led him to some very different conclusions about the purpose of that strange retreat. His siblings, he’d come to believe, had grown irritated by his successful run at News Corp. Perhaps watching their little brother strut around like a boy-king—unsupervised by the king himself—had bred resentment. In any case, he believed, they’d been agitating for Rupert to rein in James. The family counseling was, James now believed, primarily an effort to get control of him.

At the end of the retreat, Liz told me, she offered to draft what she called a “family constitution”—an attempt to codify the values by which the newly therapized Murdochs would comport themselves. The document, titled “Murdoch Principles,” was passed back and forth between Liz and James, and eventually signed by all four siblings in February 2011. It contained a series of bullet-pointed aspirations:

“We commit to undertake active dialog with each other at all times and to relentlessly communicate openly, with trust and humility.”

“We agree not to delegate to anyone matters of family communication.”

“We will be vigilant of and defend against divisiveness, either between us or that which could infiltrate from without.”

Within months, the Murdochs would be at each other’s throats.

In 2002, a British teenager named Milly Dowler went missing. Her disappearance became a national fixation; after a six-month search, she was found dead. Nearly a decade later, on July 4, 2011, The Guardian published an explosive story, reporting that journalists at the Murdoch-owned News of the World tabloid had directed a private investigator to hack into Dowler’s voicemail before publishing the contents of some of the victim’s messages.

The Guardian article was followed by a cascade of stories alleging that News of the World had also hacked the families of soldiers killed in Afghanistan and Iraq, relatives of victims of the 2005 London bombing, and the mother of an 8-year-old girl who was murdered by a pedophile. As the allegations piled up, James huddled with executives and lawyers to figure out how serious the issue was. He had never paid close attention to the company’s newspapers in London; they were his father’s preoccupation.

The alleged hacking had taken place before the newspapers were his responsibility. But James had made a decision three years earlier that now tied him directly to the scandal. In 2008, just six months after starting his new job, he’d signed off on a settlement with Gordon Taylor, a soccer executive who’d sued the company for hacking his cellphone. It didn’t seem like a big deal to James at the time—a reporter had gone rogue, a deal had been reached, and employees who knew more about the matter than he did had advised him to authorize the payment. When executives later presented him with evidence of widespread phone-hacking at News of the World, his approval of the Taylor settlement started to look like a cover-up. Over Rupert’s objections, James said, he instructed the company’s lawyers to call the police and hand over everything they had. (A spokesperson for Rupert disputed James’s account.)

Shortly after the Guardian story broke, James called his father to say they needed to shut down News of the World—the company’s most widely read newspaper—to contain the crisis. Rupert was not happy. He saw the scandal as an attack by his competitors—and the way to deal with an attack was to fight back. He instructed his son not to say a word to the press, James recalled. He’d be in London soon.

In the meantime, James became the public face of the scandal. Paparazzi camped outside his house. Pundits speculated that James might face a prison sentence. Every time Kathryn heard a siren in the distance, she was briefly gripped with a panic that the police were coming to arrest her husband.

“This is crazy!” she recalled telling James. “You cannot just sit here and hide!” He had to take control of the story.

“My father won’t let me,” he said.

Rupert’s arrival in London only made things worse. While James worked with his team on a damage-control strategy—including firings, internal compliance reforms, and an ad campaign apologizing to the public—Rupert was freelancing. He went around London answering reporters’ shouted questions, and paid a surprise visit to Milly Dowler’s parents. He told a Wall Street Journal reporter that he was “getting annoyed” with all the negative publicity, generating yet another round of negative publicity.

James was alarmed. His father looked frail and confused—nothing like the decisive, towering figure he’d long admired and tangled with. He remembers calling Lachlan in Australia and fretting, “Dude, our old man has gone crazy. This is terrible.”

To quell the public’s outrage, someone high up at the company would have to resign. To James, the obvious choice was Rebekah Brooks, the former News of the World editor who now oversaw the Murdochs’ British newspapers. But Rupert loved Brooks, and insisted that he prized loyalty. “I don’t throw people under a bus,” he reportedly said.

James’s sister had a different idea. Liz, who lived in London and had sold Shine to News Corp earlier that year, had been a constant presence throughout the crisis, offering advice and comfort to their father. At one point, while talking with Rupert in the office he’d commandeered as a war room, she made the case that a member of the family would have to take the fall—and that person should be James. He’d already been planning to leave Europe to work under News Corp’s chief operating officer in New York. Why not reframe his resignation as a kind of Murdoch mea culpa?

Rupert said he’d think about it. The next day, he told Liz he liked the idea.

Then he added, “Go tell him.”

Liz obediently made her way down the hall to James’s office. “I was chatting with Dad, and we think the only way to stop the noise is for you to step down,” she recalled telling him. James was irate. He knew his father hated familial confrontation, but this represented a new level of cowardice. He told Liz that if their father wanted to fire him, he’d have to do it himself.

The episode did lasting damage to James and Liz’s relationship. When anonymously sourced stories appeared in the press painting James as the chief villain in the phone-hacking saga, he suspected that Liz’s camp was behind them. And when Liz’s production company was dismantled and merged with two other companies in 2014, she believed it was her brother exacting revenge. The siblings barely spoke for years. More than a decade later, Liz would tell me that she couldn’t believe she’d sacrificed her relationship with James in her quest for her father’s approval. “It’s one of the greatest regrets of my life,” she said.

James eventually came to understand that Rupert and Liz weren’t the only ones trying to scapegoat him. He told me that Liz’s then-husband, Freud, had used his extensive media contacts to wage a concerted leak campaign against him with the apparent goal of making Liz the new favored successor so that he could play puppet master. (The couple divorced in 2014. Kathryn, reflecting on his behavior throughout the marriage, told me, “I cannot exaggerate what a terrible person he is.” Freud did not respond to requests for comment.)

How much responsibility did James bear for the bungling of the phone-hacking scandal? Two News of the World employees would claim under oath that they’d told him about evidence that the practice went beyond one rogue reporter and a private investigator, and that he’d ignored them. James maintains that his employees hid the evidence from him. A parliamentary investigation would find that James was, if nothing else, guilty of “an astonishing lack of curiosity.”

What’s clear is that James took the brunt of the blame. On July 19, 2011, he appeared alongside his father at a high-profile parliamentary inquiry. James tried to read from the statement he’d prepared with the company’s lawyers, but Rupert cut him off to intone, “This is the most humble day of my life.” Later, when Rupert was asked why he hadn’t fired a reporter accused of phone-hacking, he said, “I had never heard of him,” and then added, “I think my son can perhaps answer that in more detail.”

James left London in disgrace in 2012 and moved back to New York, having resigned from his job as executive chairman of the Murdochs’ British publishing unit as well as his chairmanship at Sky. His role as deputy chief operating officer of News Corp had been presented publicly as a promotion, but in reality he was on a short leash—toiling in the company’s headquarters under the watchful eye of his father.

Fourteen years later, the phone-hacking episode remains an obsession for James. It was the moment everything began to unravel, and his appetite for relitigation seems bottomless: the hit pieces that had gotten key facts wrong, the politicians and competitors who’d maligned him for sport. But whenever I’d ask about his father’s role in it all, he’d clam up. I began to wonder if he was actually protecting Rupert.

One afternoon in the spring of 2024, James, Kathryn, and I sat at the dining-room table in the couple’s grand country home in Connecticut, and I tried to get him to tell me the story again, this time without skipping the parts about his father. He kept standing up to clear the table, or asking if anyone wanted coffee, or suggesting that we move into the living room. At one point, he trailed off mid-sentence and nodded vacantly toward a window. “We had a bear in those little trees last year,” he said, to no one in particular.

Finally, Kathryn volunteered her version of events. For as long as she’d been in the family, she argued, Rupert had tried to force his two sons into a rigged competition. “He was pitting them against each other,” she said, “but there was always going to be one winner.” Every promotion James had gotten was, in Kathryn’s view, an invitation to fail, so that Rupert could validate his first choice of successor. When the phone-hacking scandal hit, Kathryn told me, “they could finally force a failure” on James.

This sounded a bit conspiratorial to me, and I wondered if James would quibble with it. Instead, he just shrugged. “I mean, you take your lumps, right?” he said. “It’s life.”

I wanted to press him on this point—to suggest that it might not actually be normal for your father to conspire to destroy your career and place you in legal jeopardy in order to give your job to your older brother. But James surely knew all this. Maybe he just didn’t want to dwell on his father’s cruelty, or the fact that he’d never been the favorite. James wasn’t protecting Rupert, I realized. He was protecting himself.

On April 22, 2015, James pulled up to the Lambs Club, a Midtown restaurant popular among media executives. He was scheduled to depart that afternoon for Indonesia, but he’d been asked to make time for a quick lunch with Lachlan and Chase Carey, one of Rupert’s most trusted lieutenants. He wasn’t expecting an ambush.

Four years after the phone-hacking scandal, the fallout was still being felt. Hundreds of victims had come forward, and millions in settlements had been paid. At least fifteen employees had been charged with hacking crimes. The company had been forced to drop its bid for Sky, and Rupert, in order to protect his most valuable brands, had split his empire in two, with the newspapers and HarperCollins under the News Corp umbrella and the U.S. TV and film assets housed in a separate company, 21st Century Fox. (Rupert remained chairman of both companies.)

James believed, however, that he was still the only plausible successor. Lachlan was happily cocooned in Australia. He and his wife, Sarah, a former host of Australia’s Next Top Model, were a Sydney power couple. Rupert had made it clear in recent years that when the time came, James would become CEO of Fox while Lachlan maintained a symbolic chairmanship role from Australia. After years of succession drama, it seemed the Murdochs had finally come to an understanding.

But James sensed that something strange was going on as soon as he sat down at the Lambs Club. Finally, Lachlan and Carey came out with it: Lachlan would be returning to the U.S. to become CEO of Fox, and James was going to report to him.

James, stunned, tried to keep his voice steady. “No, I’m not going to do that,” he remembers telling them. They could run the company without him.

He walked out and headed straight to the airport. For the duration of his trip, he ignored texts and phone calls from his father and brother. James felt that he’d earned the top job after nearly two decades of work—a belief he’d thought his father shared. To discover now that Rupert had been talking with Lachlan about coming back and claiming his rightful spot as heir apparent was too much to take. There was simply no way he was going to work under his brother.

As rumors of James’s resignation spread through the companies, anxiety started to set in, former employees of Fox and News Corp told me. James, for all his shortcomings, was the only Murdoch son who knew anything about the business. One former executive told me that losing James would have been “a disaster.”

By the time James got back to the U.S., Rupert had retreated: James would become CEO as planned, and Lachlan would be named chairman. It would all be announced that summer.

James agreed to stay. But as the announcement neared, he told me, he began to suspect that he’d been played. First, Lachlan announced that he and his family were moving from Sydney to Los Angeles. Then he began setting up an office on the Fox studio lot. By the time the reorganization was announced in June, the bait and switch was complete: Lachlan was not taking a passive figurehead role; he was going to be executive co-chairman, a title he would share with Rupert. James and Lachlan would be running the company together.

Why didn’t James quit? He told me that he was guided by a lesson from the Divine Comedy. At the gateway to hell, Dante encounters a character believed to be Pope Celestine V, who in life had abdicated the papacy to live as a hermit. His choice had been celebrated for its holiness and purity, but Dante deems him a coward for allowing evil to enter the Church in his absence.

To James, the meaning was clear: If you have a chance to wield power for good and choose to walk away, you’re responsible for what comes next.

In June 2016, days before Britain was scheduled to vote on Brexit, James attended a News Corp board meeting in London. The once-fringe idea of the country leaving the European Union had, in recent months, gotten a major boost from the Murdoch press. The Sun ran stories warning of the “GREAT MIGRANT SWINDLE” being perpetrated by EU bureaucrats in Brussels. The Sunday Times endorsed the referendum and gave favorable coverage to Boris Johnson, the floppy-haired member of Parliament, as he campaigned for the Leave cause in a bright-red “battle bus.” Opponents argued that the referendum’s passage would have dire economic consequences—but that side of the story was no fun. The Brexit movement made great copy.

At a lunch before the meeting, James was chatting with top editors, executives, and directors at News Corp when Johnson himself dropped in. He cracked jokes and regaled the group with stories from the campaign trail. When someone asked him if the referendum would pass, Johnson smirked: We’ll see!

“It struck me that everyone was just having a laugh,” James recalled. “Nobody thought it was going to win, including Johnson.”

James noticed a similar attitude in the early coverage of Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign by the Murdochs’ outlets. Like most everyone else in his orbit, James had initially regarded Trump as a sideshow. But as the candidate took off, the attitude among people inside Fox and News Corp was illuminating.

James had assumed, perhaps naively, that his older brother—Princeton-educated world traveler that he was—would balk when Trump, say, proposed banning Muslims from entering the country. But whenever James mentioned one of these outrages, Lachlan would bristle. “He immediately went to this nasty, knee-jerk, anti-Hillary stance,” James recalled. “I was sort of taken aback.” As time went on, James said, he was surprised by the degree to which his brother was apparently willing to indulge “reactionary” and “white nativist” ideas. (A spokesperson for Lachlan called this characterization false.) James never would have suspected affable, dilettantish Lachlan of being a secret ideologue.

Even more surprising to James was that his father seemed to have no ideology at all. He’d thought his father was a devoted free-marketeer, an internationalist who supported American global power, and a believer in immigration as a source of industry and ingenuity. His brand of conservatism seemed miles apart from Trump’s—and indeed, for the first few months of the campaign, Rupert was openly scornful of the candidate. He told James that if Trump won, it would “be the end of the Republican Party,” and when Fox News hosted the first debate of the GOP primaries, he reportedly ordered Megyn Kelly, one of the moderators, to hit Trump hard. But once it became clear that Trump’s appeal to Rupert’s audience was enduring, Rupert pivoted.

The Wall Street Journal ’s editorial page, a bastion of Reagan-Thatcherite conservatism, started running editorials defending Trump’s policies. The Fox News prime-time lineup became a four-hour Trump commercial. Rupert’s beloved New York Post ran covers celebrating Trump’s shredding of liberal pieties. There was no intellectually consistent way to reconcile the about-face. It was, James realized, just power and profit and mischief all the way down.

“There’s this tabloid culture that’s contrarian for the sake of it, and delights in poking people in the eye,” James said. “At its worst, it metastasizes into something nasty and scary and manipulative.” Press these cynical Trump boosters for a defense, he told me, and they would say something like “He’s not going to be president anyway—what’s the harm?” He compared the outlets to Paul von Hindenburg, the German president who in 1933 inadvertently enabled Hitler’s rise to power, earning himself the nickname “Undertaker of the Republic.”

“I underestimated the ability of a profit motive to make people do terrible things—to make companies do terrible things,” James later told me.

Then, in July, James thought he saw an opportunity to intervene. He and Lachlan were in Sun Valley, Idaho, for the annual Allen & Company media conference when news broke that Ailes was being sued by the Fox anchor Gretchen Carlson for sexual harassment. Rather than simply issue a statement of support for Ailes and wait for the litigation to resolve, James and Lachlan decided that the company should contract an outside law firm to conduct its own internal investigation.

This was not an obvious call: Ailes had built Fox News into the single most profitable asset in the Murdoch empire, and Rupert had rewarded him with wide latitude and loyalty. But Rupert was unreachable at the moment—flying back from France, where he’d been vacationing with his fourth wife, Jerry Hall—which meant that James and Lachlan had a brief window to act. Together, they decided to approve the investigation before their father’s plane landed.

Over the next two weeks, dozens of allegations would surface against Ailes. Ailes had reportedly demanded oral sex from women at work, and promised career advancement in exchange for sexual favors. (A lawyer for Ailes called the allegations false.) James wanted to fire him immediately, but Rupert insisted that it was better to let him resign.

To replace Ailes, James wanted to hire David Rhodes, the president of CBS News, who’d gotten his start at Fox News. He thought Rhodes could clean up the network’s culture and instill more rigorous editorial standards. Lachlan was fiercely opposed. After letting the brothers squabble for a while, Rupert announced that he would run Fox News himself as interim CEO.

To James, the result was predictably catastrophic. Under Rupert’s nominal supervision, the Fox News talent was free to run wild. Tucker Carlson, whom Murdoch had promoted to prime time, began airing monologues about the racist “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory (aided by a head writer for the show who was later revealed to be posting racist content under an online pseudonym). Other hosts publicly sounded off about the injustice of the accusations against Ailes.

In January 2017, the anchor Bill O’Reilly settled a $32 million lawsuit with a former on-air analyst who’d accused him of sexual harassment. When news of the payout became public later that year, Rupert and his sons said they hadn’t been privy to the dollar figure, but they did know a settlement had been reached, and had decided to renew O’Reilly’s contract anyway.

In June 2017, British regulators punted on approving the Murdochs’ second bid for Sky, James’s longtime dream acquisition. The regulators cited anti-trust concerns, but James thought he knew the real reason: He was now presiding over a company that was known around the world as a scandal-ridden propaganda machine for Donald Trump.

James and Lachlan tried to project unity as they ran Fox together. But in reality, James told me, the power-sharing was a disaster. Inside the company, Lachlan hated any suggestion that his younger brother was the more seasoned executive. And James grew exasperated by Lachlan’s certainty about the ins and outs of a company he’d left a decade ago. “You don’t develop the capabilities necessary for running large, complicated companies by osmosis,” James said.

Both brothers, who were based on opposite coasts, had to sign off on every major decision, James said—and Lachlan was often conspicuously unavailable when needed. He skipped meetings, and would go days without responding to certain texts and emails from James. People who observed the brothers’ dynamic were mystified. “It was like parallel play,” a former employee told me, “but one of them wasn’t playing.”

Then, in August 2017, torch-bearing white supremacists marched through Charlottesville, Virginia, chanting, “Jews will not replace us!” In the days that followed, the cable-news channel that James ostensibly ran spent hours defending Trump, who had asserted that there were “very fine people” marching with the neo-Nazis.

James wanted to say something to his employees about Charlottesville. But he also knew how it would look to his father and brother: pious, nagging James once again shoving his personal politics in everyone’s face. He dreaded the prospect of arm-wrestling with Lachlan over every word in the statement, as the brothers had earlier that year when they issued a companywide memo responding to Trump’s travel ban. (James had wanted to reassure their Muslim employees and oppose the policy; Lachlan insisted on watering it down.) Maybe, James thought, it wasn’t even worth trying this time.

Finally, Kathryn asked a clarifying question: “If you’re not going to stand up against Nazis, who are you going to stand up against?”

James decided to put out his own statement without consulting Rupert or Lachlan. In an email sent to friends, and promptly leaked to the press, he denounced the protesters in Charlottesville as well as Trump’s reaction to them. “I can’t even believe I have to write this: standing up to Nazis is essential; there are no good Nazis,” he wrote. He and Kathryn would be donating $1 million to the Anti-Defamation League, and he encouraged others to join them.

The couple thought Rupert might speak out, too. He had long considered himself a proud opponent of anti-Semitism, and had even once been honored by the ADL. But Rupert remained silent, as did Lachlan.

By the fall, James wanted out. The situation with his brother was becoming untenable. Lachlan had no interest in James’s reforms, and James could no longer look away from the effect that Fox News was having on both U.S. politics and the reputation of the broader Murdoch enterprise.

Around this time, Rupert began talking with Disney’s chairman, Bob Iger, about a potential sale of the 21st Century Fox film and TV studio. After decades of empire building, Rupert was coming to terms with the fact that Fox wasn’t big enough to compete in the streaming wars with Netflix, Apple, and Amazon. Better to whittle down the company to his first love—news—and cash out on everything else.

James knew a sale would give him cover to leave the company without causing too much speculation about the family’s growing rifts. It would also mean a payday for major shareholders, himself and his siblings included. He threw himself into the negotiations.

As the Disney deal took shape, however, Lachlan became more and more hostile to it. He grumbled that he’d moved his family from Australia to Los Angeles so he could preside over a proper media empire. Now they wanted to off-load its most glamorous asset and leave him with a collection of shrinking TV stations, cable channels, newspapers, and book imprints that, according to one former News Corp employee, he referred to as “ShitCo.”

Over dinner one night at Gramercy Tavern with James and Rupert, Lachlan—usually so friendly and unflappable—lost his temper. He shouted threats and ranted about his opposition to the deal, James recalled. Before storming out of the restaurant, Lachlan delivered an ultimatum: If you go through with this deal, he told Rupert, “you will not have a son.” Then he turned to James and added, “And you won’t have a brother.” (A spokesperson for Lachlan called James’s version of events false.)

Years later, when James looked back on Lachlan’s prophecy, he would call it an “Oracle of Delphi moment.” In the end, a brother and son would be lost—just not the one they thought.

The deal closed on March 20, 2019: Disney would purchase 21st Century Fox for $71.3 billion. As an apparent concession to Lachlan, the studio lot—where he kept his office and rock-climbing wall—would remain in the Murdochs’ possession. Within a few years, the price that James helped negotiate would be widely seen on Wall Street as a coup, with some analysts estimating that Disney had overpaid by as much as $20 billion. James and his siblings each received roughly $2 billion.

The day the deal closed, James and Kathryn contributed $100 million to their foundation. Its offices were in Lower Manhattan, two floors above James’s new investment firm, Lupa Systems. The firm was named after the she-wolf in Roman mythology who nurses the twin boys Remus and Romulus—one of whom goes on to kill the other to become the first king of Rome.

In January 2020, a reporter for the Daily Beast reached out to James. Australia was experiencing a devastating series of bushfires that were widely seen as a consequence of climate change—but in the Murdochs’ Australian news outlets, that notion was treated as absurd. The Daily Beast reporter wanted to know what James thought of the coverage. It was the kind of question he’d always ignored—but this time felt different.

Since stepping down as CEO of 21st Century Fox, James had retained his seat on the News Corp board. But now that he was no longer heir apparent, he found, his father’s courtiers and loyalists did not appear to be gripped by his views. One day, while sitting in a board meeting, he’d begun making a list of all of the investments, reforms, and initiatives he’d pushed for, only to be shot down or ignored. Looking at the list, and around the table, he thought, What am I doing here?

James had his spokesperson give the Daily Beast a statement: “Kathryn and James’ views on climate are well established and their frustration with some of the News Corp and Fox coverage of the topic is also well known. They are particularly disappointed with the ongoing denial among the news outlets in Australia given obvious evidence to the contrary.”

The quote angered the News Corp board. In May, James was told that if he didn’t resign his board seat, he risked being voted off—an outcome he’d expected. He resigned.

A wave of media speculation followed. Dynastic drama was in the ether; Succession was gearing up for its third season. The show’s popularity had created a life-imitating-art-imitating-life phenomenon: All the fictionalized on-screen scheming led to conjecture in the press about real-life scheming among the Murdochs, which seemed in turn to induce higher levels of paranoia within the family.

Observers had long understood that Liz and Prue were liberals who disagreed with the rightward tilt of Rupert’s outlets, while Lachlan was a man made in his father’s image. James was always the unknown variable. Now that he was adopting a publicly antagonistic posture, pundits were predicting that he and his sisters would team up once Rupert died, boot their brother from the corner office, and finally domesticate News Corp. Words like coup were getting tossed around in the press, and Rupert suspected that James himself was working to promote the narrative. (According to James, Rupert didn’t think Liz or Prue could possibly have been the ringleaders. “He doesn’t believe his adult daughters are capable of making decisions,” James told me.)

James would later tell me the idea was ridiculous. No secret conspiracy existed among himself and his sisters, he insisted. Besides, if they were plotting a coup, why would James want it broadcast in the press?

But disabusing his father of this conspiracy theory wasn’t easy, because the two men were no longer speaking. Their estrangement hadn’t been a conscious choice. James had simply found that there wasn’t much to say to each other anymore—work had always been the foundation of their relationship. Now Rupert’s perception of his younger son was shaped more by what he read. James was becoming a problem.

James was still finding it difficult to stay away from the family business. In 2022, Rupert announced plans to recombine Fox and News Corp, and asked his four oldest children to sign a letter recommending the merger. They were to promise, among other things, not to sell any of the companies’ assets, regardless of how much was being offered.

Surely it wasn’t in shareholders’ best interest, James thought, to uniformly rule out any future offer. His sisters, and the directors who managed their trust, shared his concern. But when one of the directors, Richard Oldfield, raised it on an email thread, Rupert erupted.

“Sorry Richard! This has been a family dominated business for seventy years,” he wrote. “It would be a disaster for at least the US and Australia if these assets fell into the wrong hands.” Rupert believed that a transaction that gave liberals control of any piece of his empire would amount to an intolerable blow to his legacy.

But James was worried that the recombined company would be less valuable than it was divided in two. Before signing the letter, he requested additional information about the directors’ fiduciary responsibilities in the matter. Rupert responded by griping that James and his sisters were throwing up legal obstacles and told Liz that he might just “ram it through.”

The boards for Fox and News Corp had set up committees to study the merger, and James decided to write them each a letter detailing his concerns. James heard that the letters infuriated his father and brother. But he was vindicated, in January 2023, when Rupert was forced to abandon the merger amid a revolt by shareholders. More vindication came a few months later, when Fox announced a $787.5 million settlement with Dominion Voting Systems. In the weeks after the 2020 election, Fox News had repeatedly aired false claims that Dominion’s voting machines had rigged the election against Donald Trump. Now, as a result of the reckless conspiracizing, the network’s parent company was paying one of the largest-known defamation settlements in history.

The final phase of the Murdoch family crack-up, as best James could tell, began with a woman named Siobhan McKenna.

A longtime friend and confidant of Lachlan’s, McKenna served as his managing director in the family trust. Her fierce loyalty had helped make her one of the most powerful media executives in Australia—CEO of News Corp’s Australian broadcasting arm, chair of the Australia Post, and managing partner at Lachlan’s private investment firm.

In the summer of 2023, McKenna approached Lachlan with a proposition: She believed she could devise a plan that secured Lachlan’s future control of the companies and permanently sidelined James without necessitating an expensive buyout. Lachlan, intrigued, told her to start working on it. (McKenna did not respond to requests for comment.)

On September 14, 2023, Rupert, Lachlan, and a consortium of Fox and News Corp executives gathered to hear McKenna’s pitch for Project Family Harmony. The family trust, they all agreed, was untenable as it was currently structured.

Lachlan had by now spent years building the case to his father that James was plotting a coup. In the fall of 2022, an unauthorized biography of Lachlan had been published in Australia containing an incendiary quote from an anonymous source about James’s purported plans: “Lachlan gets fired the day Rupert dies.” When the quote made international headlines, Lachlan told Rupert that James’s camp was responsible. A few months later, in January 2023, the Financial Times ran a story detailing “how the scions could battle for control” of the family trust after Rupert was gone. Once again, Lachlan pointed the finger at his brother.

As it turned out, according to evidence that would later surface at trial, James had no involvement in either story—but Lachlan did. It was McKenna who had, with Lachlan’s approval, spent more than 14 hours giving anonymous interviews to the biographer. And Brian Nick, an executive at Fox, had anonymously briefed the Financial Times. (Nick denied providing information to the Financial Times.) But to Rupert, the stories only confirmed that he needed to act decisively.

In October 2023, Kathryn told James that she thought he should reach out to his father and brother. They’d barely spoken in years, and though she didn’t yet know about their plans for the trust, she worried that Rupert and Lachlan were sinking too deep into their own conspiracy theories. James never got around to calling them. Later, he would wish he’d taken her advice.

Over several weeks that fall, the participants in Project Family Harmony explored a range of aggressive options to neutralize James. PowerPoints were prepared; legal memos were produced. James was rarely invoked by name in these materials; he was referred to as “the troublesome beneficiary.”

Rupert ultimately decided that the best course was to negate the voting power of James and his sisters. To do this, Rupert would have to amend the Murdoch family trust to give Lachlan unilateral control after he died. And because the trust was irrevocable, with amendments allowed only if they were in the interest of the beneficiaries, Rupert would have to show, in effect, that disenfranchising three of his children was actually best for them.

McKenna drafted talking points for Rupert to use when discussing the amendment with his children. New directors were also secretly recruited to the trust, including Bill Barr, the two-time attorney general and a personal friend of Rupert’s, and a pair of lawyers who had scant experience with trust management but had the advantage of being politically connected in Nevada, where the inevitable litigation would play out.

Meanwhile, James and his sisters—unaware of Rupert and Lachlan’s plotting—were making plans of their own. On September 20, 2023, they met in London to discuss arrangements for after their father’s death. Liz’s managing director, Mark Devereux, had realized that the Murdochs didn’t have a logistical plan for such a scenario. Who would release a statement? What would it say? What kind of funeral did Rupert want? A plan had been drawn up and code-named “Project Bridge,” after the protocols developed for Queen Elizabeth II’s death.

In London, as the siblings talked through the details, their conversation turned to the long-term future of the companies. Prue asked James if he wanted to return as an executive, but he told her he had no interest.

In late November, James, Liz, and Prue were invited to join a “special meeting” on Zoom to discuss the trust. When Liz found out what Rupert and Lachlan were about to do, she texted Lachlan and pleaded with him not to go through with it. “Today is about Dad’s wishes,” Lachlan responded. “It shouldn’t be difficult or controversial. Love you.”

A less dysfunctional family, James and Kathryn told me, might have tried to have a normal conversation about their differences. Instead, in the Zoom meeting, on December 6, Rupert, surrounded by lawyers, read robotically from a script. Lachlan busied himself at an off-screen laptop and didn’t even look at the camera.

Early on the morning of September 16, 2024, a fleet of black SUVs pulled up to the copper-domed Washoe County Courthouse in Reno. James and Kathryn stepped out of their car and made their way up the steps alongside Liz and Prue. About 30 minutes later, another convoy appeared, this one carrying Rupert and Lachlan. The Murdochs had coordinated their arrival times to ensure that they didn’t have to see one another outside the courtroom. Nobody wanted the half a dozen camera crews to capture evidence of the hostility that now defined their family.

James and his sisters had filed their objection shortly after learning about their father’s amendment. The process had revealed, among other things, just how far apart James and his father were in their visions for the family’s media outlets. During James’s confrontational deposition, for instance, one of Rupert’s lawyers suggested that the success of Fox News derived from its willingness to pander to its viewers, sometimes at the expense of basic journalistic standards.

Isn’t it true that Fox is the top cable-news outlet because it respects its audience and gives them what they want? the lawyer asked him.

I would disagree with the idea that respect and giving people what they want are the same thing, James countered.

But the lawyer didn’t seem interested in the distinction. Are you aware that Fox News lost a significant part of its audience when it called Arizona for Biden in 2020? he asked. James said he was. And you know that Fox won back most of that audience through its election-denial coverage, right? the lawyer said.

Now, for the next six days, the two sides would make their case in court, testifying about some of the most painful episodes in the Murdoch family’s history as they wrestled over control of the empire. Rupert didn’t stick around to watch it—he was excused from the courtroom after testifying on the second day. “He claimed that he was sick, but I think it was cowardice,” James told me.

The trial was closed to the press and public, and because Kathryn was not a party to the litigation, she waited in an anteroom with Liz’s and Prue’s husbands. After long days of testimony, the families would convene at a Lake Tahoe house that James and Kathryn were borrowing from friends (“There are no good hotels in Reno,” she told me) and recap the day’s events over glasses of wine. Sometimes there were dramatic reenactments; other times they indulged in gallows humor. They searched Google for Edmund Gorman, the Nevada probate commissioner overseeing the proceedings, hoping to ascertain any biographical details that might reveal his sympathies. He was frustratingly unreadable during the trial: They knew he wore polka-dot bow ties under his robes, and someone had reported seeing him once leave the courthouse in a loud purple sport coat. They learned that he was a duck hunter, and that he’d served on the board of the Reno Jazz Orchestra. This last fact prompted James to observe to his sisters, “He can’t be that bad.”

James had resolved to approach the trial in a spirit of combat. “I’m good at that,” he told me later. “Stiffen your spine, harden your tummy.” Walking into the courtroom each day, past the scrum of reporters, he wore an expression of solemn professionalism. But it was harder than he’d expected to maintain personal detachment when the people on the other side of the courtroom were his father and brother. Watching these men he’d known his whole life, men he’d loved, he couldn’t escape one thought: How did we let it come to this?

On the third day of the trial, James took the stand to testify. When he recounted the dinner at which Lachlan effectively ended their relationship over the proposed Disney deal, James surprised himself by starting to cry. But the memory didn’t seem to have the same effect on his brother, James told me: When Lachlan was asked if he had in fact told James he wouldn’t have a brother anymore if they pursued the sale, Lachlan responded flatly, “I don’t recall.”

A month after the trial’s conclusion, while the commissioner was still deliberating, James decided to reach out to his father. The trial had gone well for him and his sisters; their lawyers were confident. Still, he knew the damage to his family might never be undone. Thanksgiving was approaching, and James was feeling sentimental. Maybe, he thought, his father might be open to a personal appeal, especially now that he looked to be on the verge of defeat.

James, Liz, and Prue wrote their father a letter suggesting an alternative course. “Thanksgiving and Christmas are upon us and the three of us wanted to reach out to you personally to say that we miss you and love you,” they wrote. “Over and above any other feelings all of us may have—of upset and shock—our unifying emotion is sorrow and grief.”

Maybe they could try to talk things out without lawyers and probate commissioners—and reach a compromise they all agreed on: “We are asking you with love to find a way to put an end to this destructive judicial path so that we can have a chance to heal as a collaborative and loving family.”

A couple of days later, Rupert wrote back. He’d read his children’s testimony from the trial twice over. “Only to conclude that I was right,” he told them. He instructed them to have their lawyers contact his if they wanted to talk further. “Much love, Dad.”

On December 7, the commissioner issued his ruling. Rupert and Lachlan had lost.

The commissioner’s decision placed the fate of the Murdoch assets back in the same holding pattern it had been in for years. Barring a successful appeal, control of the companies would, in all likelihood, one day be split evenly among the four oldest children. Only now Rupert’s heirs were more divided than ever, with the chosen successor on one side, and his three alienated siblings on the other. What exactly that would mean for the empire was a question that wouldn’t be answered until their father died.

In the meantime, James and Kathryn have focused on projects of their own.

It’s hard to look at the couple’s political and philanthropic work, which Kathryn manages, without sensing an attempt at public repentance. They have given millions to Democratic campaigns and tens of millions to climate-change initiatives, and funded research on disinformation and political extremism. In 2021, Kathryn persuaded dozens of “democracy reform” groups to coalesce around the push for open primaries and ranked-choice voting, funding successful ballot initiatives in Alaska and Washington, D.C. James, meanwhile, is once again doing business in India, where he has invested in one of the country’s largest media companies. He has also bought large stakes in the Tribeca Film Festival and Art Basel.

What would the Murdochs’ conservative news outlets look like if James had his way? This had become a central question in the legal battle over the trust; Rupert and Lachlan argue that James would sink the companies’ value by changing the outlets’ politics.

James and Kathryn were usually cautious when I asked about changes they would want to see at the family’s news outlets. But I got glimpses of their thinking. Once, over dinner in Washington, Kathryn told me she wasn’t sure if Fox News could still be reformed. “It doesn’t have a clear purpose in the ecosystem anymore,” she said.

On another occasion, I asked James if The Wall Street Journal ’s editorial page might serve as a model for a more responsible Fox News. He winced and said he hoped they could do better than that. At various points, both of them mentioned their investment in The Bulwark, which was founded as an organ of Never Trump conservatism, as proof that they weren’t categorically averse to “center right” media—though, of course, reinventing Fox News in The Bulwark’s image might be the surest path to a viewer revolt.

The one thing James has said consistently is that any reforms he might seek would focus on corporate and editorial governance, not political orientation. Fox News, he thought, could still report from a conservative perspective without, say, giving a platform to unqualified doctors to spread medical misinformation during a pandemic, or misrepresenting an oil-company shill as an expert on climate change. James believed this wasn’t just the right thing to do, but the fiscally prudent one: Allowing Trump’s former lawyer Sidney Powell on air to spread voting-machine conspiracy theories had already cost Fox three-quarters of a billion dollars, and an even larger defamation suit was still pending. (James stressed that reforming the outlets would require support from the board.)

For now, James is left struggling to answer the question he found himself asking in the courtroom—how did we let it come to this? His 93-year-old father will, despite his most fervent wishes, die one day. And when he does, he will leave behind a family at war with itself—a bevy of estranged children and ex-wives exchanging awkward greetings at an expensive funeral.