One of the most infamous scenes in Eraserhead involves an unusual family dinner. Henry (Jack Nance) joins his girlfriend Mary (Charlotte Stewart) for a meal with her parents, in a blue-collar apartment in the film’s unnamed industrial city.

Mary’s father (Allen Joseph) invites Henry to cut the main course, a set of miniature roast chickens. Despite the father’s instructions to “cut ‘em up like regular chickens,” the poultry begins writhing as soon as Henry’s fork pokes it, spewing a grotesque bile while waving its wings and legs. A pulsing, squishing noise accompanies close-ups of the bird, soon matched by the sound of Mary’s mother (Jeanne Bates) going into a seizure or trance.

The camera cuts from the wiggling, bleeding birds to the participants at the table, catching Henry’s helpless look of confusion and Mary softly crying.

The dinner scene is one of the most infamous moments in Eraserhead, the 1977 debut feature by David Lynch. Fans cite it as an example of the film’s bizarre, upsetting tone and imagery, a twisted look at the American family.

Upsetting as the bleeding bird and undulating mother certainly are, the scene isn’t played just for shock. There’s a genuine sadness to the moment, which the camera acknowledges in the vulnerability experienced by Mary and the confusion felt by Henry. As strange as the Eraserhead scene is, it’s also deeply human and humane.

This infamous Eraserhead moment captures the strangeness that has continued to be a defining feature of Lynch’s work. However, it also captures one of the most important, yet still under-discussed aspect of Lynch’s oeuvre: his unrelenting empathy.

Weirdness for Emotion’s Sake

Perhaps the best encapsulation of the public perception of Lynch’s work can be found, perhaps unsurprisingly, in The Simpsons.

In the season nine episode “Lisa’s Sax” from 1997, Homer sits and the couch and watches Twin Peaks, or at least a cartoon approximation of the show, complete with jazzy score and a Kyle MacLachlan sound-alike. On the screen, a white horse dances with a Giant sporting a bowtie, while a stoplight swings from a branch.

“Brilliant!” Homer laughs. “I have absolutely no idea what’s going on.”

As always, Homer speaks for many. They recognize that Lynch is doing something in his work, and it works for them on an emotional level, but they can’t articulate why. Well, most can’t articulate why. Some put together lengthy explanations to nail down the meanings behind the key in Mulholland Drive or the white horse that appears in the Palmers’ living room. They think that Lynch’s weirdness is either a challenge that must be overcome or an idiosyncrasy to be tolerated.

Both of these approaches make it almost impossible to truly engage with Lynch’s work. Take his very first film, the four-minute short “Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times)” from 1967. The short student film consists of about forty-five seconds of animation, which plays on a loop as an air-raid siren blares. At the top of the frame sit the heads of six men, with a tube running to exposed stomachs below, surrounded by black ink that fills up two-thirds of the frame. The men wave their hands as red bile fills their stomachs and then turns the color of a bruise. The black ink turns purple as the men vomit, just to have the whole thing start all over again.

It would be easy to dismiss “Six Men Getting Sick” as weirdness for weirdness’ sake or a type of abrasive outsider art, and many do. However, Lynch’s art works best on an emotional level, and while the emotions in “Six Men Getting Sick” might initially push people away, they also call for sympathy. After all, the men, the lone recognizable and human figures in the film, are suffering. There’s no end or reason to their suffering. It just happens, again and again.

The same is true of nearly every weird or upsetting scene in Lynch’s filmography. Take one of the most infamous moments in his work, the figure behind the Winkie’s dumpster in Mulholland Drive.

Nothing about the scene makes any sense. It involves two characters who don’t appear in any other part of the movie (played by Patrick Fischler and Michael Cooke), who meet in a diner to discuss a dream that one of them has had. After hearing about the dream, the two walk out to the dumpster behind the restaurant, so that one can prove to the other that it isn’t real. When they arrive to the dumpster, a filthy figure materializes from behind a wall, accompanied by a sting that turns her appearance into a chilling jump scare.

The scene is terrifying, but the terror works because we viewers sympathize with Fischler’s unnamed character, who collapses in fright at the sight of the woman. We don’t know who she is or how she got there, but we do know what a suffering person looks like when we see one. We’re scared because he’s scared, because we sympathize with him.

From Eraserhead and The Elephant Man to The Straight Story and Inland Empire, this visceral sense of empathy drives Lynch’s work. When Isabella Rossellini’s torch singer Dorothy Vallens emerges from a house nude and screaming in Blue Velvet, when Dune villain Baron Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan) cackles after killing an innocent young man, when vain leading man Lester Guy (Ian Buchanan) cringes at the inexplicable success of starlet Betty (Marla Rubinoff) in the little-loved comedy On the Air, there is a vulnerable person at the center, experiencing emotions both recognizable and profound.

Ineffable Feelings Finding Each Other

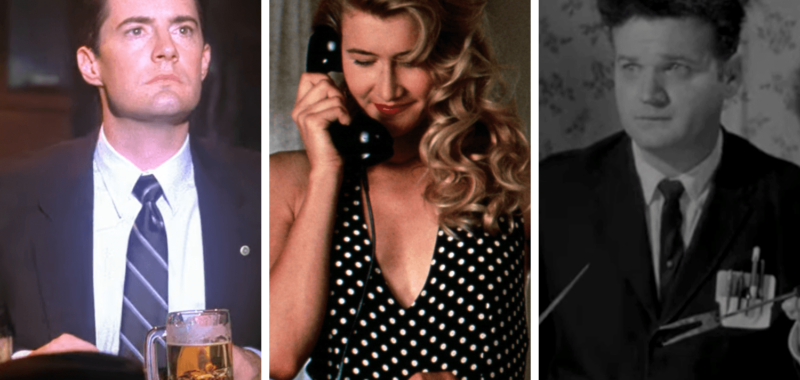

In the fourteenth episode of Twin Peaks, just before the infamous reveal of Laura Palmer’s killer, several of the main characters gather at the local watering hole, the Roadhouse. FBI Agent Dale Cooper (MacLachlan) and Sheriff Harry Truman (Michael Ontkean) sit among the crowd of onlookers to watch singer Julee Cruise perform, while troublesome teens Bobby (Dana Ashbrook) and Mike (Gary Hershberger) sit at the bar. Young lovers Donna (Lara Flynn Boyle) and James (James Marshall) make eyes at each other in a booth.

Midway through the song, the band disappears and the Giant (Carel Struycken), one of the figures who so baffled Homer Simpson, takes their place on the stage. “It is happening again,” the Giant tells Cooper. The episode then cuts to Laura Palmer’s house, where Laura’s cousin Maddie (played by Sheryl Lee, who also portrayed Laura) is beaten to death by Laura’s father Leland (Ray Wise).

When we return to the Roadhouse, the Giant fades away and the band returns. Only Cooper has seen and heard the Giant’s message, but a palpable sorrow fills the bar. Cutaways find Bobby, Donna, and others bursting into tears, unable to understand why. An elderly man (Hank Worden) comes up to Cooper and says, “I’m so sorry.”

There’s no explanation for the mechanics of what happens, nor does there need to be. The point is that something so awful has happened that it cannot be contained by logic or reality. It defies conventional wisdom, and so Lynch breaks rules and reality to express it.

As far as Lynch’s strange moments go, the breakdown is one of the easier to take. But the principle is true, even when it comes to his most upsetting scenes. With its overheated characters and stomach-churning dramatic beats, Wild at Heart might be the most disturbing entry in Lynch’s filmography. It’s hard to see anything human in Willem Dafoe’s grotesque Bobby Peru or Crispin Glover’s Santa-obsessed Jingle Dell.

But none of these characters drive the narrative in Wild at Heart. Instead, they serve as examples of a twisted, hateful world, which only underscores the purity of the love between protagonists Sailor (Nicolas Cage) and Lula (Laura Dern). We viewers might be bothered by the sight of Lula’s mother (played by Dern’s real-life mother Diane Ladd) smearing her face with lip-stick, but the underlying emotion still connects: she fears that she’s losing her daughter, while Lula desperately longs for a more accepting form of love.

Weird as these people are, they are still people, deserving of empathy.

Sitting in the Strangeness

The dinner scene in Eraserhead captures the feeling that some viewers when they watch Lynch’s work. They feel like they’re stuck in a world that they don’t understand, and they want nothing more than to run from the room, like Mary’s mother does at the inexplicable sight of writhing chickens.

Yet, Mary’s mother comes back. She comes back and demands that Henry stay with Mary. Whether or not that’s a good move for anyone isn’t the point of the scene. The point, rather, is the very real and very understandable feelings of everyone involved: Mary’s embarrassment and guilt, the mother’s desire to protect Mary in some way, and Henry’s overwhelming sense of responsibility.

That conflict ultimately takes the form of a grotesque monster baby that plagues Henry throughout the rest of the film. How the baby works doesn’t make sense. What the baby is doesn’t make sense, and Lynch still won’t explain how he constructed the prop.

But what does make sense is the way it suffers, the way Henry tries to help it and then gives into potential for violence when all else fails. Even at its most surreal and disgusting, the Eraserhead baby, Henry, and in fact all of Lynch’s characters call for empathy, even if it’s an empathy that transcends logic or reason.