Brandi Carlile is picky about voices — “very picky,” she says, “and strange, and specific” — which is probably why she’s surrounded herself with the same ones for more than 20 years.

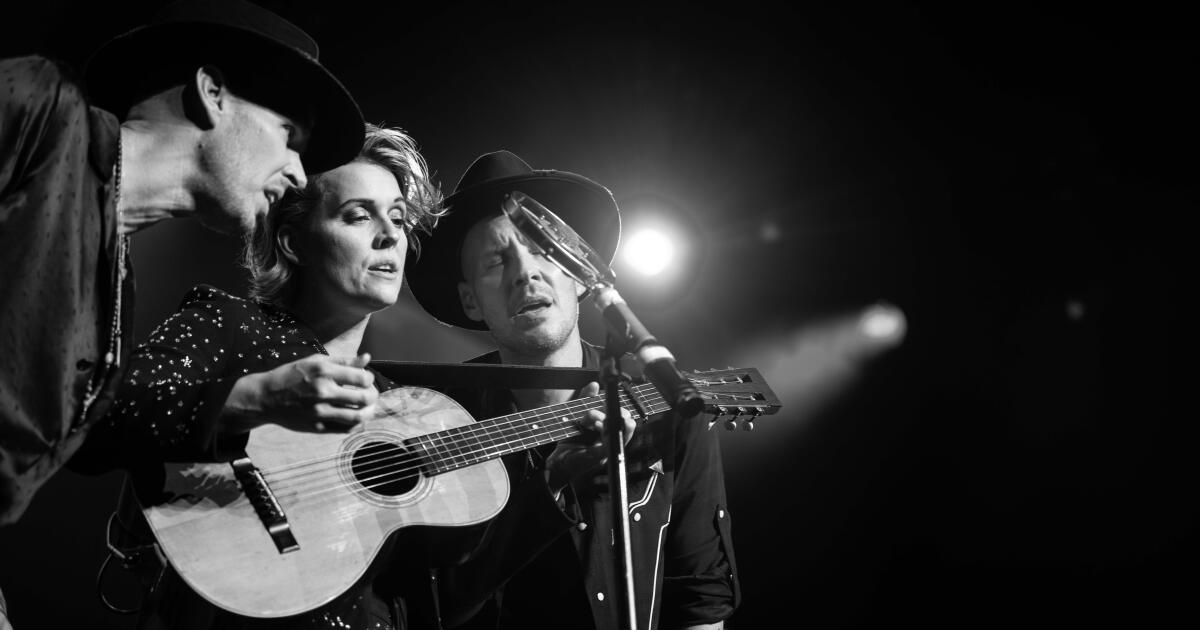

Since the early 2000s, the singer-songwriter from Washington state has written, recorded and performed as a member of the three-person band she calls Brandi Carlile with Tim and Phil Hanseroth, identical twin brothers who play guitar and bass, respectively, and add harmony vocals behind Carlile’s show-stopping instrument.

“He’s pointy and honky and harsh,” Carlile says on a recent afternoon, nodding toward Phil. “And he’s crazy and low and mellow,” she adds, nodding toward Tim. “One sounds like Cat Stevens, one sounds like Chris Cornell, and together they only sound like the twins.”

Says Tim with a smile: “That’s something where we can both feel like we got the better end of the compliment.”

Now, after seven Carlile studio albums — and 10 Grammy nominations, including multiple nods for album and song of the year — the siblings are stepping out on their own with a debut LP, “Vera,” credited to the Hanseroth Twins.

Well, almost on their own: Carlile served as an executive producer on the album, which balances intricately fingerpicked ballads with stately folk-rock numbers, and this year she’s had the brothers opening shows for her on the road. (Carlile also contributes backing vocals to the stirring “I’ll Always Know I Do.”) Yet “Vera” offers a welcome showcase of the Hanseroths’ bone-deep musical connection.

Carlile and the twins sat down on a recent afternoon at the Sunset Marquis to discuss the album and their intertwined careers — and to build some anticipation for the concerts they’ll play with Joni Mitchell at the Hollywood Bowl on Oct. 19 and 20.

A few years ago, Tim, you told me that Brandi has a light switch that she flips when she goes onstage to access her inner diva. Brandi, how are the twins different in front of an audience versus not?

Brandi Carlile: That’s kind of what I wanted to find out. In our band, there is no difference — these guys’ll wear those skintight pants to do yard work. On their own they have to find a persona to settle on that is who they are onstage. They have to talk between songs, for one thing.

Tim Hanseroth: We don’t say a lot onstage with Brandi.

Carlile: You don’t say anything!

What has Brandi taught you over the years about performing?

Tim: Oh, God — everything. She has such a way with words, and she just knows how to pull people into her story.

Carlile: They watched me learn how to do that. I remember going out and opening for Howie Day and Ray LaMontagne in the very early days and getting in the van at the end of the night and going, “Guys, I’m just not breaking through — I gotta learn how to talk between these songs.” Then we went on tour with Shawn Colvin, who just talks the whole time, and I started learning some comedic timing.

Brandi, you first encountered the twins when they were playing in their old rock band, the Fighting Machinists.

Carlile: They were famous in Seattle. Everybody knew who they were.

Was the fact that they were twins part of the appeal?

Carlile: It was jarringly cool, the charisma of their identicalness. They had these blond haircuts, great tattoos, rail thin, just walking around looking like supermodels. The first time I saw them was across the room in a bowling alley. I was already out of the closet, a little baby dyke, and I remember telling my sister, who’s now married to Phil — I was like, “Look at those two.” They looked liked they’d walked off the cover of Seventeen magazine.

Phil Hanseroth: I wish I’d known that back then.

Carlile: They just didn’t look like everybody else. They were sparkly — fairy dust came off them everywhere they went.

Why didn’t it happen for the Fighting Machinists outside Seattle?

Tim: We were a great band, but we were very loud with very little to say. We had these two big Marshall stacks and this wonderful wall of grungy sound, but there wasn’t a ton of emotional substance in there.

I’m not sure that was an impediment for Candlebox.

Carlile: The Candlebox drummer was our drummer for a while. I lived at his house.

Tim: I just don’t think we’d done the living yet to really write a song that would connect emotionally with people.

Carlile: It was also the very tail end of [the ’90s Seattle rock frenzy]. They were boarding up the windows of the record labels in downtown Seattle. It was changing, and the twins just didn’t get there in time. Thank God.

You both were in your mid-20s when the band broke up. Did that feel young enough in rock ’n’ roll years to find a new path?

Tim: Absolutely.

Carlile: They even separated, the two of them, a little bit. Phil joined a punk band from Philly called the New Black. And me and Tim started bonding musically. But the whole time, I was like, “We gotta get your brother.” Phil was like, “I don’t know…”

Phil: Well, you called one night and you guys were opening for Vienna Teng or something. I was like, “Dude, I was just making out with a chick in the middle of the street in Portland.”

Carlile: It was also weird for a bass player to join two acoustic guitar players — though I think that’s the cornerstone of what our band sounds like now. It made his bass lines really melodic and unique and strange.

You’ve said that making “Vera” grew out of a decision to dial back Brandi’s touring for a while.

Tim: It started as like a COVID hobby that we eventually put aside. Then, when we decided to spend less time touring, we thought it was a good time to pick it back up. But it’s also an opportunity to go learn some things that we can bring back into the Brandi Carlile band.

Carlile: Our real periods of growth have always been when we’ve taken a risk that threatens the shape of our trio.

What’s a previous example?

Carlile: [Producer] Dave Cobb writing “The Joke” with us. That was the first time we ever had another person come into our little agreement, and at the time I don’t think anybody knew how to make room for it. We’ve been impenetrable to drummers. We’ve alienated wives and family members [laughs]: “I’m not hanging out with Brandi and those f—ing twins. Those guys don’t let anybody into their jokes. They don’t let anybody into their songs.” But we don’t have to keep the shape. We can do these things and then snap right back to our triangle.

Tim and Phil, you didn’t grow up immersed in the world of roots music that you’ve found a home in with Brandi. What was it like to absorb that tradition?

Tim: It was like finding another book in the set of encyclopedias. We’d always liked Gordon Lightfoot and some of the folk stuff. But, like, Johnny Cash? Before we met Brandi, that was just a name I’d heard. Never listened to that growing up — not even close. I can’t actually remember hearing a country song except for maybe “The Devil Went Down to Georgia.”

Carlile: They would also say s— like, “We don’t listen to women’s music.” They weren’t being misogynist — they just hadn’t heard much. I was like, “This is gonna be a great van ride, then, because we’re gonna go through the entire Lilith Fair lineup for the last three years.”

Phil: Emmylou Harris I remember hearing for the first time in 2005 or something.

Carlile: I played Indigo Girls for them: “Listen to the harmonies, guys — it’s like Simon and Garfunkel, but they’re lesbians.”

“Vera” includes a very pretty cover of “A Little Respect,” the great late-’80s synth-pop hit by Erasure. To my mind, Erasure was never as big, at least in the States, as it should’ve been. Why is that?

Phil: They were ahead of their time and people weren’t ready for it.

Carlile: Ahead of their time in so many ways: spiritually, musically, technologically. When I was young and didn’t have much access to pop culture, I didn’t know that [singer] Andy Bell was any less important than Freddie Mercury. But they were much more camp than Queen.

Phil, were you responding to the camp aspect when you discovered Erasure?

Phil: I’m not sure I was really thinking about that.

Carlile: Well, Phil’s kind of camp.

Tim: He’s wearing a mesh shirt.

Phil: I’ve never been kicked out of a place for being too masculine, I’ll tell you that.

Carlile: Remember we used to tease you about having your legs crossed all the time?

Phil: In fact, you used to call me Bitch Lips.

Carlile: He always had his f—ing ChapStick and he was always doing his lips. We’d be taking photos for a fan: “Hang on, hang on…”

The three of you live with your families in separate houses on what you call a compound near Seattle. Clearly, you believe in its benefits. What’s a drawback?

Carlile: That no one can move.

Phil: If one person moves, the whole thing crumbles [laughs].

Carlile: The only real drawback I can think of is that the mountain we all look at, they’re clear-cutting it right now. So we’re looking at a molehill. But it’ll be green again some day.

Would you have imagined as a kid that you’d live this way?

Tim: Honestly, yeah, as a best-case scenario. I actually think it’s the way that people are meant to live — closer, more communal. People have coexisted like that for 200,000 years or more.

Carlile: I can feel a little silly as a woman in her 40s explaining to people that everyone I love is on top of me. But not silly enough to change it. It’s because we live on top of each other that I push a little harder to have us find our way out in the world as individuals. I’m writing another book. They’ve done this album. Tim almost tried out for the f—ing Smashing Pumpkins.

Tim: They got a way better guitar player than they would have with me. I don’t know if I would’ve lasted anyway.

Carlile: He didn’t end up trying out because they were looking for somebody for more than a tour.

Tim: Big commitment.

I can’t let you go without saying something about Joni Mitchell at the Bowl.

Carlile: The tea I can spill is that I’ve spent these last five, six years in the passenger seat with Joan, and in this case I’m in the backseat. She’s chosen to learn songs that I never heard before, that have been an incredible challenge for us all to learn. It’s gonna be a long show. She wants to give everybody a full-spectrum performance of who she really is and what her career has done. It’s different than [Mitchell’s shows at the Newport Folk Festival and the Gorge Amphitheatre] — it’s gonna be even crazier. I’m seeing her be inspired in ways I haven’t seen before. And we’ve got some people that have joined the party that are just an inspiration to watch work.

Phil: Probably half the songs on our next record are gonna be in weird tunings because of working with her.

Carlile: He’s having to do [bassist] Jaco [Pastorius’ parts] on songs where Jaco tripled his bass. Phil’s got to play all the licks — and not piss off Joni in the meantime.

Phil: You can’t get anything by her.