“Of course you changed nothing. The world is only improved by people who do ordinary jobs and refuse to be bullied. Nobody can persuade owners to share with makers when makers won’t shift for themselves.”

—Lanark, 554

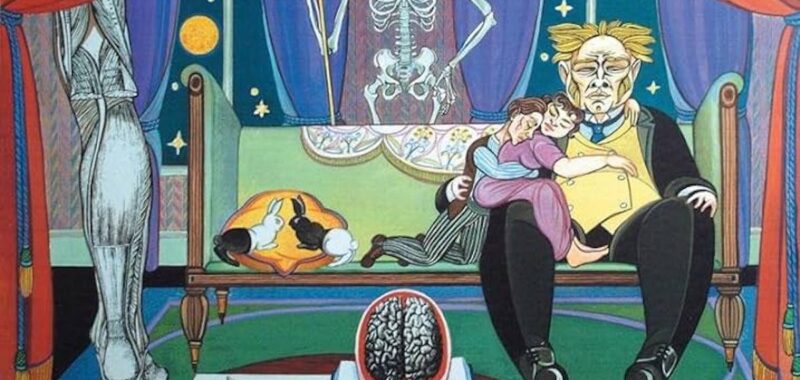

Alasdair Gray was a key figure of Scottish literature in the late 20th century, a socialist, and a talented visual artist, some of whose murals can still be seen around Glasgow today. But while his importance to the landscape of Scottish literary fiction has long been acknowledged, he is less frequently acknowledged as one of the great imaginers of the fantastic. Some of this is no doubt due to Gray’s magpie approach to genre. Within the same text he’ll happily mix elements of biography, literary fiction, fantasy, metafiction, and art and design. Gray incorporated his line drawings into his books, meticulously designed the layout of the words and images on the page, and even insisted on having control of the cover art for his books, much of which he created himself. He was fond of formal experiments, pushing what text on a page could do, sometimes to its very limits, with a cheerful playfulness. All this makes Gray’s individual books absorbing works of art in and of themselves, as objects—and no doubt causes massive headaches to publishers trying to make his work available in ebook or audiobook format. They are uniquely compelling and immersive experiences, if occasionally frustrating and opaque.

Yet none of this should discourage the adventurous reader of genre fiction. While it’s possible to quibble about exactly how to categorize his work, in my opinion Gray published at least four key works of fantastic/speculative fiction. His debut novel Lanark (1981) is a towering achievement of the fantastic, in which the fantasy city of Unthank and the real-life Glasgow that Gray grew up in during the post-war period are both mirror images of Hell. Poor Things (1992), recently adapted into a film by Yorgos Lanthimos, is a postmodern reimagining of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) that relocates the original to Gray’s beloved Glasgow and uses its metafictional framing to pose feminist questions about narrative and agency. A History Maker (1994) is Gray’s most explicitly science fictional text, exploring life in a future post-scarcity socialist utopia which comes under threat from extremists. And his first short story collection, Unlikely Stories, Mostly (1983), demonstrates Gray’s skill at crafting Borgesian metafictional puzzles and charming fables in equal measure. Together they demonstrate a body of work that engages with the science fictional and the fantastic in innovative and playful ways.

Lanark

Until the council sends us the decimal clocks it’s been promising for so long Unthank is virtually part of the intercalendrical zone. At present the city is kept going by force of habit. Not by rules, not by plans, but by habit. (437)

Lanark is the book that made Gray’s literary reputation when it was first released, and in some respects remains his most important achievement. A massive ambitious epic, over four books Lanark tells the story of Duncan Thaw, a working-class artist growing up in Glasgow after World War II, and of Lanark, whom Thaw becomes after his death, a man with no past who finds himself in the magical city of Unthank where there is no sun, the people are subject to bizarre mutating diseases, and life is controlled by a Kafkaesque bureaucracy. Books one and two chart Thaw’s life, whilst books three and four tell Lanark’s story, but they’re placed out of order (as are the Prologue and Epilogue). The novel actually begins with book three, enveloping the realist depictions of Thaw’s life in Glasgow with Lanark’s life in its fantasy equivalent Unthank. But much of the genius of Lanark comes from its sheer disregard of genre boundaries—the novel incorporates semi-autobiographical realism, surreal fantasy, and a metafictional section where Lanark meets Gray himself, and only acknowledges boundaries between them in order to poke holes in them.

Lanark should be mentioned in the same breath as Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren (1975), M. John Harrison’s Viriconium stories (1971-84), and Jeff VanderMeer’s City of Saints and Madmen (2001) in terms of great metafictional stories of the urban fantastic. Unthank is a place where time doesn’t follow the normal rules, where you can be infected by a rash of mouths or start growing dragon skin, where the government is in thrall to a malevolent creature, but in its own way Gray’s Glasgow is every bit as wondrous, grotesque and surprising. This sense is encouraged by Gray’s heightened prose, in which the mundane details of Thaw’s life are described with as much vivid hallucinatory intensity as Lanark’s journeys through the underground labyrinths of Unthank. The way that Lanark’s story mirrors and refracts Thaw’s life, with elements of Unthank clearly echoing elements of Glasgow, provides a brilliant commentary on the fantastic’s relationship to reality. Unthank is not an allegory for Glasgow anymore than Lanark is an allegory for Thaw, nor are they metaphors. Rather they are shadowy extensions of their realist counterparts which, through their inhabiting of the imagination, show us deeper truths about the real world.

Of course, Gray’s big trick is that his “real” world is as much a fabrication as the world of Unthank, something acknowledged by the novel’s forays into metafiction. When they meet, Gray and Lanark immediately begin arguing with each other, with Gray resenting his own creation and Lanark interrogating his creator’s ethics and competence—he even accuses Gray of writing bad science fiction, much to Gray’s chagrin! All this happens alongside “an index of diffuse and imbedded Plagiarisms,” in which Gray points out his influences by explaining where he “plagiarized” elements of the text to create his novel, referencing everyone from Carl Jung and Franz Kafka to William Blake and Lewis Carroll. Yet even this is complicated by Gray’s inclusion of imaginary texts alongside real ones, and his continuing of the index beyond the end of the book—in an imaginative flourish, the fates of the surviving characters after the end of the novel can be worked out from Gray’s indices that extend beyond the end of the book. Like both Unthank and Glasgow, Lanark itself is a sprawling, labyrinthine city of a book, mesmerizing and enticing, but one in which the reader is in danger of becoming lost.

Poor Things

As I said before, to my nostrils the book stinks of Victorianism. It is as sham-gothic as the Scott Monument, Glasgow University, St. Pancras Station and the Houses of Parliament. I hate such structures. Their useless over-ornamentation was paid out of needlessly high profits: profits squeezed from the stunted lives of children, women and men working more than twelve hours a day, six days a week in NEEDLESSLY filthy factories; for by the nineteenth century we had the knowledge to make things cleanly. We did not use it. The huge profits of the owning classes were too sacred to be questioned. To me this book stinks as the interior of a poor woman’s crinoline must have stunk after a cheap railway excursion to the Crystal Palace. (275)

After a series of less well-received works, Poor Things revitalized Gray’s career, and remains one of his most popular books. The novel is the author’s reimagining of Frankenstein, transposed to 19th-century Glasgow. But of course, being Gray, it’s not quite that simple. The novel purports to be Episodes from the Early Life of a Scottish Public Health Officer by Archibald McCandless, M.D., a book published by a vanity printing press and rescued from a skip by one of Gray’s historian friends. Poor Things is a wonderful gothic comedic romp of a story, in which the young doctor McCandless falls in love with Bella Baxter, a woman who has been “created” by benevolent mad scientist and McCandless’ friend Godwin Baxter by taking the body of an anonymous drowned woman and bringing it back to life using the brain of the woman’s unborn fetus. It’s a thoroughly charming story in which Bella resists being influenced by the cynical male figures who surround her and claims her own agency as a woman and a doctor, defying the expectations placed on her gender; eventually, she happily marries McCandless, very much on her own terms. However, this is all immediately contradicted by another note found with the original text, a letter from Bella herself, or Victoria as she is calling herself by then, long after her husband’s death, where she decries the entire story as contemptible nonsense. Both texts are annotated by Gray himself, who purports to believe McCandless’ account, whilst his historian friend sides with Bella’s rebuttal.

The brilliance of Poor Things lies in how Gray pits these two voices against each other. The reader is sucked into McCandless’ story, despite its melodrama and ridiculousness, because it is fun and charming, and Gray is clearly having a great time playing with the gothic form. But crucially, Gray gives Bella her own voice, allowing her to talk back to all the men who have tried to “create” her, either through controlling her education, directly trying to control her life through traditional patriarchal bonds, or by controlling the narrative in which she appears. She reminds the reader of the conventions of Victorian and gothic storytelling that shape McCandless’ narrative, and the political assumptions they reinforce, particularly about gender and class. These contradictory takes on the same history, which are then editorialized upon by Gray and his historian friend, remind us that all narrators are inherently unreliable, that all texts are constructed within a base set of assumptions, that storytelling itself is an inherently political act.

A History Maker

“When a lot of folk watch something on a screen they all see the same thing. What a damnable waste of mind! Readers bring books to life by filling the stories with voices, faces, scenery, ideas the author never dreamed of, things from their own minds. Every reader does it differently.” (140)

A History Maker is set in a 23rd-century Scottish utopia, in which the technology of household powerplants that can generate any object desired brings capitalism to an end. Wat Dryhope is a hero from the wargames that occupy the men whilst the women of the future run the world. Chaffing against his reputation and the expectations foisted upon him by the society in which he lives, he becomes embroiled in a plan by a group of radicals to use a global war to reinstate capitalism. The main text of the novel tells Wat’s story, but it is prefaced and annotated by Wat’s mother, who received the text from Wat himself before his disappearance, and who is writing these historical notes many years after the failure of the radicals’ plot.

Much has been made of Gray’s influence on other Scottish writers, and in particularly the great Iain M. Banks, who also straddled the worlds of literary and genre fiction. It might be a bit of a stretch to call A History Maker Gray’s attempt at a Culture novel, but it does feature a far-future socialist utopia under threat by malevolent forces, and the shadowy secret society that fights to defend it. It’s just that in this case, the shadowy secret society aren’t Special Circumstances or sentient starships, they’re Scottish grannies sitting round a campfire telling stories.

Gray brings his usual inventiveness and playfulness to exploring the science fictional ideas of utopias and post-scarcity society, but imagining a society built around traditional Scottish forms of storytelling rather than interstellar travel. Even more so than Poor Things, A History Maker reflects on unreliable narrators—both Wat and his mother are telling their version of the story to achieve very specific political aims, and we are reliant on their worldviews to explain to us the reader how this far future society works, with all the baggage that their viewpoints come with. Thus, whether it is us reading the book in the novel’s distant past, or the implied future reader reconstructing their own history from Wat’s story and his mother’s annotations, we are made aware that the tools we are given to grasp the world of the novel contain their own implicit political biases.

Unlikely Stories, Mostly

For a moment the wheel of the civilized world was joined to the wheel of heaven. The disaster which fell a moment later was an accident nobody could have foreseen or prevented. I am the only living witness to this fact. I have been higher than anybody in the world. The hand which writes these words has stroked the ice-smooth, slightly-rippled, blue lucid ceiling which held up the moon. (77)

Gray wrote many short stories in his life, amounting to seven collections, which these days can all be found in the huge anthology Every Short Story, 1951-2012. His short fiction frequently engages with the fantastic, perhaps more directly than his novels, but still retains his joy at experimenting with form and metafictions. In this way, they bring to mind the works of Italo Calvino and Jorge Luis Borges, albeit with Gray’s trademark Glaswegian wit. All his collections are worth reading, but much of his best work in the short form, and his most fantastic, can be found in his debut collection, Unlikely Stories, Mostly. As with his novels, Gray took great care with his collections, so many of his stories are accompanied by his striking line art, which adds to the poetic, haiku-like beauty of the text. Into this category falls “The Star,” a charming tale about a boy who finds a fallen star, “A Unique Case,” about a friend who suffers a head injury that reveals he has tiny men working in his brain, and “The Spread of Ian Nicol,” in which an ordinary riveter grows another version of himself out the back of his head. These stories are charmingly whimsical, and beautifully manage to root the bizarre and the inexplicable in the everyday, working-class Glasgow that Gray lived in, using only a few pages and some inventive illustrations.

Other stories are longer and more ambitious. “The Comedy of the White Dog” mixes folklore and sexual farce, whilst “The Great Bear Cult” is a bonkers alternate history about a cult of bear worship that sweeps Britain in the 1930s, told through the format of a script for a faux-documentary. It is the five linked stories that make up the final two-thirds of the book that are the real meat of the collection. These stories are bookended by “The Start of the Axletree” and “The Fall of the Axletree,” an extended riff on the Tower of Babel, in which the ruler of a powerful empire with nowhere left to expand realizes the only way to keep the empire growing is to divert all resources into a grandiose project, a tower that will connect the ground with the sky. The first story chronicles how the emperor comes across the idea and sets his people into building the Axletree, while the last story tells of its inevitable hubristic downfall after it reaches the surface of the sky. The stories in between are kind of implied to be set in the same world. “Five Letters from an Eastern Empire” is perhaps Gray’s most well-realised short story, the tale of a man selected to be a poet in the far Eastern empire—on the other side of the world from the empire building the Axletree—whose illusions about the rightness of the state and the emperor are gradually stripped away as he learns about the horrific costs of empire building. “Logopandocy” is the most radical story in the collection, another riff on the Tower of Babel and an exploration of the decay of language in which language itself collapses over the course of the story, leaving nothing but gesture at the end. And “Prometheus” is a retelling of the myth of the Titan and bringer of fire embedded in the story of a man trying to retell the story of Prometheus as a play. This cycle of stories is as powerful and ambitious as any of Gray’s novels.

Gray was a writer whose restless creativity and disregard for genre boundaries led him to frequently engage with fantastical and science fictional ideas. They were tools to be played with, as much as metafiction or autobiography or any of the other techniques and genres Gray would use over the course of his career. His books are tributes to his unbounded imagination and to his love of books as objects of art in their own right. While they can sometimes be messy and daunting, there’s no doubting his ambition. At his best, his books are immersive works of art for the adventurous reader to get lost in, meticulous constructions that reflect the bizarre and confounding worlds contained within. He was one of Glasgow’s key literary voices, and the fantastic was an essential part of how Gray put literary Glasgow on the map. All of these works, and Lanark especially, offer a singular experience that any fan of literary fantasy and the urban fantastic should be eager to embrace.