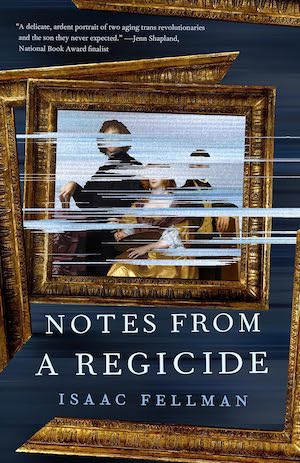

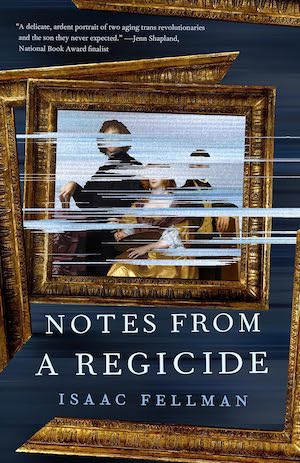

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Notes From a Regicide by Isaac Fellman, a heartbreaking story of trans self-discovery with a rich relatability and a science-fictional twist—publishing with Tor Books on April 15, 2025.

When your parents die, you find out who they really were.

Griffon Keming’s second parents saved him from his abusive family. They taught him how to be trans, paid for his transition, and tried to love him as best they could. But Griffon’s new parents had troubles of their own – both were deeply scarred by the lives they lived before Griffon, the struggles they faced to become themselves, and the failed revolution that drove them from their homeland. When they died, they left an unfillable hole in his heart.

Griffon’s best clue to his parents’ lives is in his father’s journal, written from a jail cell while he awaited execution. Stained with blood, grief, and tears, these pages struggle to contain the love story of two artists on fire. With the journal in hand, Griffon hopes to pin down his relationship to these wonderful and strange people for whom time always seemed to be running out.

FOREWORD

I saw my parents at a riot once. I think of it when I hear them speak, in my mind, of love as a tool. A lot of things were tools to them, not because they wanted to control the world, but because they were skilled craftspeople and their tools were the best way they had of understanding and using it. There were good tools and bad ones, sharp and dull, some for daily use and some for nightly. Others were so obscure that they were only useful once a year, or once a lifetime. At least one was never used.

It was during the riot at the Sauce Pot. A lot of people claim to have been at the Sauce Pot, and it’s easy enough for them all to be right. The battle went on for six hours, and lasted through waves of reinforcements. But this was at the beginning, when the riot was fairly fresh—the coffee already thrown and the doors already barricaded, but still time for two elderly, precarious immigrants to do a little damage and make their escape.

I hadn’t even known my parents ever went there. It was a place I associated with trans people much rougher than them. By that point in their lives, they were of the rich class of any oppressed minority that more or less gets away with everything, and which rarely mixes anything but money into the communal cup. Beyond that, my mother was an agoraphobe who never left their sleepy, filthy house unless she had to. But she must have had to that night, because when I arrived to cover the riot for the New York Greatheart during the blooming of its second hour, there they both were. They were the first thing I saw.

I was running through the blue alley on the far side of the building from the canal. People don’t remember how big a place the Sauce Pot was. It was a converted warehouse, with plenty of room to swing an arc of hot liquid—coffee or lava or piss. I could see the sign, the golden pot boiling over, through the corner of the side and front windows. From inside I heard talking and tinkling and sweet laughter, delighted laughter, and I thought of a play I had seen—about the sinking of a ship—where a simulacrum of a heavy instrument panel broke free of a wall and was supposed to crush two men to death. Well, I thought the crushing looked cozy. You may as well die with something wrapped tight around you. What I heard inside the coffee house was pressed out of a human body by a great weight.

I came round the corner and there they were. Zaffre’s back was full to me, her loose cotton dress flapping in the strong wind from the canal. Etoine was kneeling on the ground. Half in panic at seeing them so far from their context, I stepped back into my alley to watch.

A spurt of a giggle escaped Zaffre. Then there was a very soft sound of something slapping against water, something big and evenly distributed. I looked around the corner and saw that Etoine had stepped off the dock into a boat, and that the boat was a low-slung police cutter. He was concentrating—I saw his pale wrists twisting something, and then Zaffre said quite loudly, “Look out now, a butch has a multitool.”

“Pshe,” he said, and “shh.” But his voice was as delighted as hers had been. Then there was a loud noise of bubbling, and the boat began to sink under him—to visibly and quickly sink—and he stood erect in it as you’re not supposed to do in a boat, and in one motion she stooped and picked him up, a hand beneath each of his armpits, and her shawl flew away and sank into the water, all of which she ignored, for she was looking into his eyes.

Zaffre possessed tremendous physical strength. She was a real Jeanne Valjeanne, as Etoine periodically called her (always waiting for her broken short-term memory to reset before he said it again). I am an athlete and I can lift—oh—a good deal on a good day. I ought not to tell you how much, because this book will be read when I am old and can’t lift much at all, and I don’t want to lie to you. It is not easy to hold a full-grown man in front of you with extended arms. Etoine was not the smallest of men, and Zaffre was not an athlete, either. Her only exercise was painting, although of course she attacked that with force, and her hard breathing alone sounded like work. But no matter how sedentary her life was, or how much estrogen she took, nothing could break the line of her shoulders. She might have liked her strength or resented it, when she was younger. Nowadays she took it quite for granted, and used it as casually as a machine uses its torque.

Now Etoine, suspended for a moment above the empty river, said calmly, “There. Done.”

Buy the Book

Notes From a Regicide

She got his cane into his hand and they walked off, not too quickly and not too slowly. I went on to the front of the building, passing a policeman running back to the sinking boat, and I took advantage of his absence to knock at the window. They opened the barricades to let me in, and I stumbled into a hot and welcoming room, where smashed crockery and sugar glittered on the floor. More than one person showed me where Etoine had stitched up their wounds in clean sewing-kit thread. Later, when they broke down the doors, I sat under a table with my press pass around my neck, taking notes and learning that tear gas sinks. The work I did that night won me a Hallam Prize.

The next time I saw Etoine and Zaffre, they were sitting at their kitchen table sharing a block of new chocolate from the awful tea shop he loved. Whatever new chocolate there was, Etoine bought it. It was candy that cost four times what it should have, whose texture was dense and sharp. Etoine was saying, “It tastes like dirt, but fancy dirt.”

Zaffre said, “It tastes like… soil.”

“Soil,” Etoine agreed, and hearing me in the hall he half-turned on his stool and said, “Griffon, you have to try some of this shit. It’s delicious, and it tastes like soil.”

“Soil!” Zaffre repeated, and they cracked up.

When I told them about the riot, they listened with great interest, but did not tell me they’d been there. On the contrary, Etoine said, “These people, my first instinct is to worry that they’ll get in so much trouble. After all this time, it’s still so hard for me not to be afraid.”

“Oh, if you’d been there, you know you would have raised hell,” said Zaffre.

Etoine shrugged. “I guess in the moment, I usually do. I just always expect something to stop me. That’s the trouble I’m afraid of—as if God will stop me. But if God wanted us to not raise hell, he would’ve made natural laws against it. You can’t go mistaking a human law for a natural law.”

“You don’t believe in God,” said Zaffre.

“I don’t really believe in laws either,” he said, and took another bite of the candy.

* * *

Who were these two people? Revolutionaries, or half-revolutionaries. Survivors, or half-survivors. They spoke a language that was half one thing and half another, and they had spent half their lives together. I was always conscious that I had half their attention.

I was not related to them by blood. They took me in when I was a terrified child, and smothered me with affection because they could not reach me in any less violent way. I reacted, in turn, like a smothered person.

They were, as I have said, immigrants. Refugees, really, although since they were rich and comfortable when I met them—no longer starving artists—I often forgot it. Long ago, forty years ago now, they fled from Stephensport in the far north. Stephensport was a city-state, a principality, which was always renamed for its ruling prince. Five hundred years ago it was called Francoisport and a thousand years ago it was called Liesenport, and before that it was called nothing in particular. And when they left it, they came to New York, the eternal city, which five hundred years ago was called New York and a thousand years ago was called New York, and in another thousand years will be called New York still. You can’t kill my city, though Etoine and Zaffre played a small but important role in killing theirs.

* * *

She killed herself, too. He died of cancer. She went first, when they were seventy-two; he followed four years later. This thought must always be a part of my book, just as it is always a part of my life. I can give you so many numbers. Etoine was twenty-four years sober; he was twenty-four years on testosterone. They married, by the powers vested in the New York Department of Immigration, when they were forty-three. They met when they were fifteen, and I met them when I was fifteen.

None of these numbers means any more to me than the casualty figures after a disaster, when three thousand, twenty-three thousand, a hundred thousand deaths all feel about the same. The numbers have nothing to do with the pulse of my family, which is uncountable, a furious asynchronous beating, a throb out of control. It is this throb which I wish to capture in the rhythms of this book. Its pistons, its broken machines.

* * *

When I assembled raw materials for this book, I thought I would base much of it on Etoine’s diaries. That was before I read them. They were working documents only—intended to aid in his sobriety. Repetitive and angry, they mostly recorded incidents of temptation. One representative entry, which was written a decade after his last drink: “A block from the house at Lalani’s bar, they’ve put up a printed sign that says ‘You don’t need forty whiskeys. You need one. But we don’t know which one, so we have forty.’ They don’t know how the FUCK many whiskeys I need.”

I have known many alcoholics in my time, but none like Etoine. Most of them find ways to live without drinking, come to feel that a drink is not close, but far as I can tell, he was white-knuckling it until he died. After he quit, his knuckles never took on blood again. These diaries, which he used to keep his grip, bore the marks of his hands, greasing the surface and wearing the paint away. They are too personal to publish, and frankly too uninteresting to anyone who doesn’t love him. Instead, I have based my parents’ New York story largely on my memories.

For the story of their lives in Stephensport, I have relied upon Etoine’s prison memoir. He wrote it when he thought that Zaffre was already dead, and he had nothing ahead but death on the gallows. He had no idea that he would live for decades after that, would outlive her again, would mourn her again.

Autoportrait, Blessé is what he called it: Self-Portrait with a Wound, or Self-Portrait, Injured. Nothing to do with the English “bless” or “blessing,” though you could be forgiven for thinking it, if you imagined my father had any hand for the sliding bow of a multilingual pun, or if you imagined he felt blessed.

I went through his desk when he died and found all of these writings (Zaffre left none behind, or vanishingly few). They are the ingredients for the book I am writing now. He would find that metaphor too homely, but I, unlike my parents, am a cook. They look like ingredients, too: notebooks thick with interleaved drawings, wrapped in shiny brown leather like chicken skin; small parcels of old paper tied with string like roasts ready for the oven. Something organic about them. Autoportrait, Blessé was written out on thin newsprint-like paper, already very brittle now. He has drawn on the pages, around and sometimes directly on top of his thick, dense handwriting. The drawings hide the words, and his words hide more. He never wrote a word that didn’t obfuscate another word. His words canceled each other out, as if each one precisely overlapped the two on either side of it.

* * *

I have cut and edited Etoine’s book heavily, because he wrote it deprived and manic with want. He cannot rest in this manuscript for a minute without exclaiming about all he’s not got: bits of old rubber swept along the streets, slum houses painted the heraldic colors of their aristocratic owners, the light weave of a yellow shawl with the sunshine blowing through it, the tongue-tip taste of a bowl of gelato or a glass of wine. Much of this is beautiful to read, but it makes the book exhausting, many small droplets coming together in a wave of rage and hunger.

None of this was ever in the foreground of the man I knew. Etoine was a witty and sophisticated painter, an enthusiastic reader, a taker of naps and a treasurer of props, old jewels, fresh cake. I knew he could be angry, I knew he was often numb under the glitter and bluster, but I never knew that he could ache so. Nor did I understand, in my heart, that he had spent his youth in a fairytale city, the fever-dream of people who lived thousands of years ago and had still not died.

* * *

A note on the translation. Etoine wrote in his native language, Portois. Portois is a small language; it is spoken nowhere else on earth. It descends from English as it was spoken a thousand years ago, and French as it was spoken sixteen hundred years ago—the French of the old Quebecois, for Stephensport is in that part of the continent. It is mutually intelligible with contemporary English and French, but only just.

When they came to New York, they picked up English words from the people they met—artists, queers, old Jews—and came to speak it well. It remained something clumsy, though, heavily accented, made of thick wool, since they had not really learned English so much as drifted towards it. They often spoke Portois when they were alone with me, and I drifted towards it in my turn.

I abhor both the phonetically rendered accent and the convention of noting “he switched to Portois; she switched to English” in spy novels and novels of suspense, and so I have rendered both the Autoportrait and their dialogue entirely in English. If at times their language seems peculiar to you, you may imagine that they are speaking my language in their awkward way. If they grow eloquent, you may imagine that they are speaking in Portois. You may not always be right. Zaffre’s Portois was expressive but unpolished, her English limited but literary. But you will have a general sense of it all. Of course, all of this labor has made them sound a good deal like me, but I also sound a good deal like them; they have influenced me.

Perhaps you’ll take issue with my methods. I don’t care. Perhaps Etoine and Zaffre would have, and that matters more. But they are dead, and so I will translate them as I like. If there is an afterlife, and they take issue with my decisions, I am eager to discuss the matter with them there.

And that is all I have to say, by way of preamble. Except this: there is another world under this one.

PART 1

Stephensport

CHAPTER 1

Etoine

Griffon’s notes: Should be sure to make notes at the top of his chapters, to keep the timeline clear. With Etoine, there’s always a lot to clarify. God, his words are radioactive in my hands. I don’t know how to start.

Autoportrait, Blessé begins:

Day 17 in captivity.

The more I think about it, the more I realize it all started with the portrait. Oh, of course, it’s obvious that it started with the portrait. That’s why Stephen noticed me and swept me into his world, and that’s why the city recognized its power and rose up. But I don’t mean the revolution or any of that. I mean Zaffre and me.

Zaffre and I met when we were still children. I had spent my youth avoiding her—well. I shall say “her,” because that was the pronoun she died in. But I did not know then that she was a woman. In any case, I had spent my youth avoiding her, and the clumsy, sticky, solid friendship she offered. I didn’t know why, except that she admired me so much and painted so much better than me, so it felt like mockery. She would follow me, even, loping along behind me, making nervous repetitive conversation, cracking her knuckles. I never wanted her around. I wanted to go home and get drunk in my room. Drinking was tight and secure, a band about my chest, and Zaffre was something else, something loose and uncontrolled, but hot, too, cauterizing. I have never met another artist whose brushstrokes were so like knowing them.

I can’t press my face between her shoulder blades. I can’t help her out of bed to the bath. I can’t viciously, gleefully fuck her, either in the morning or at night. So I’ll write about her, although I don’t know how, just to help her live another few months. I want her life to stretch out until the end of mine, but I know that all I have to offer—since I will die soon myself—is what the wave can offer to the shore. A brief drenching, then withdrawal, and the sun dries it, and that’s the end.

But I have one advantage, the one any good liar does: I believe. Because I’ve lived in the nameless city, the one that’s revealed when you take the name “Stephensport” away. I’ve seen her in its streets, fleetingly, and I’ve heard more of her life there. And although the nameless city had only a brief life upon this earth, it still goes on inside of me, and in it, Zaffre is alive.

* * *

The moon was heavy and full the night we dug up Sebastienne. Sweaty with light, a parody of the sun. It lit the sky around it into a blue twilight the color of Zaffre’s name. You shouldn’t do this kind of work except in darkness. You shouldn’t do it at all. None of the things I’m about to write should have happened. But, you see, I was in such trouble.

In my early twenties, I drank constantly, aimlessly. Alcohol liked to shove parts of me out of alignment. At any time, I would realize that some aspect of my body was doing things I didn’t ask it to. My fingertips would tremble; my brain would pull a little out of its socket. Parts of the day would crumble in my hands. Later, I would learn to paint within my drunkenness, but I didn’t know it then. That was why I worked as an icon painter, a failure’s work.

You’d think this would be a prestigious job, but the point of icon painting is not the skill of the painter; it is the freshness of the impression. We went to the stone yard, uncovered the electors in their eternal sleep, scrawl-sketched their faces, and painted over them later. People needed the immediacy of the sketch. There was so little left of the electors that everyone was starved for the littlest raw bit. But they needed the paint, too, to cover up the wet disaster of those faces.

This commission, however, was not for an icon. It was for a portrait of a woman who’d been born only forty years ago, and who had been placed beneath the stone yard at astonishing risk and expense, by her parents, after she had offended the prince of our city. They’d hoped she could come back after he was dead. In fact, he outlived her, though only by a few hours. Sebastienne Antoninos—I still remember your parents, polite and clean and almost mad. You can’t grieve a person who’s alive, but you can’t feel close to someone who’s asleep. The result is a suspended grief, and I suppose that was why they asked me to help, with my damaged nerves and my sharpened vision.

* * *

I lived close to the stone yard, in a scowling little building crowned with net-like fence. My small window looked out over several rows of similar houses before arriving at the glitchy, apocalyptic flatness of the yard.

The indigo sky was oppressively solid. The yard’s fence enclosed its patch of it with a feeling of tension, a high electrical whine. I knew this place well in daylight, and my feet automatically avoided the queasy softness where the stones lay over living flesh. The clients had provided good directions to where among the thirty-three electors Sebastienne slept, and I had my fingers around the first stone when I noticed someone else coming through the fence.

This was Zaffre. And here my memory splits. I remember the person I thought she was, the person she looked like: a man with a square ugly face, blank and fierce like a mastiff’s, with dry yellow curls which could not be contained by a black hooded jacket. A silent young man, who spoke with mouth almost closed over swollen-looking teeth. She walked straight over the stones, ignoring the paths of matte red that were supposed to show you the places between bodies—it wasn’t as if they felt it, but the wobbly impiety of it was all Zaffre, and gave me a begrudging thrill.

“The Antoninoses hired you, too?” I asked her.

“There’s no law against hiring two of us.”

“There is against hiring one of us.”

Zaffre gave me an impatient look and knelt to stack the stones that covered the sleeping body. They made soft clacks as we placed them to our sides; the night grew more oppressive, but never deepened beyond that square of thick extraordinary blue. The streets around the stone yard were quite silent. At last Sebastienne came into view, and I felt a chord of anxiety. I gathered my sketchpad with a sudden hand; Zaffre, always more phlegmatic, took delicate hold of the next stone and lifted it away. A blue-lit jawline was revealed, and the shadow of a neck. It was a fine neck, slender and long, and the pulse in it beat slow—you could see the blood travel up and down in long quiet labor. Zaffre cleared the stones from the hair, which was pale and wiry and moved stiffly in the breeze.

The sockets were full of soft-packed dirt, and there was dirt on the face and in the nostrils. Thank God the mouth was closed. Zaffre brought out her sponges, I mine, and without speaking we went about the quick business of dusting the filth and plugs away, like a makeup job in reverse. Then we took our pads and began to draw the face.

A blotchy arrangement of shadows in the dirt became a blotchy arrangement of shadows on the page. It was a stern face, aristocratic, severe—all the Antoninos features, the same as both parents. I believe she was an Antoninos on both sides.

Then the cold eyes opened. The face focused into an expression of gently mocking intelligence, of a humor that was unforgiving but sweeter than it should have been. Around me, the world dropped away. None of them had ever woken before. I’d thought it couldn’t happen—that there must be some special priestly technique to doing it. She laughed once, faintly, like the sigh of the wind. I was too drunk to be afraid, though Zaffre visibly was, and her busy hand fell around the pencil. I had never been in love, but I felt as if someone I loved had just woken, the face available again after a night of distance.

The motion was no more conscious than a baby’s—merely a habitual trying-out, an experiment with limbs, and I tried to work it into my sketch, but it didn’t fit and I knew I’d have to redo it at home. We had no time left before the fresh air began to take effect and waken her; Zaffre was already replacing the stones that had rested over her forehead.

We pushed through the fence and Zaffre grabbed me by the shoulder, uncertainly, as if my shoulder were just stuff—a piece of matter without known properties. I shook her grip off, from reflex only, because I was afraid. The hand came loose. Neither of us could say anything, but we began to walk together towards my place. At my door I stopped, and Zaffre turned her large light eyes to me. Still I could not speak. She turned and rushed down the road to her own house.

I trudged through the courtyard, looking in a puzzled way at the weedy lawn, jewel-dark in this rainy winter, answering the saturated sky. Inside, I lit a candle, then got under the covers of my gray bed and took up my sketch, reworking it from memory, which is often so much realer than life.

Excerpted from Notes From a Regicide, copyright © 2024 by Isaac Fellman.