2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) Directed by Stanley Kubrick. Written by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke. Starring Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, and the voice of Douglas Rain.

My cats hate this movie.

Not because, as you might suspect, the opening sequence chooses to dramatize the evolution of apes while ignoring the natural superiority of cats. Their hatred is focused entirely on the film’s sound design, and specifically those few parts of the movie where alarms and/or mysterious radio transmissions are so sudden, so loud, and so piercing that they remind both animal and human viewers of what happens when an apartment building fire alarm goes off at 3 a.m. and the human has to wrestle the animals into their carriers to lug them outside to wait for the news that it is yet another false alarm.

My cats hate this movie, but I don’t. I like it.

I want to state that up front because people get really weird about this movie. I can’t even count the number of articles and reviews I’ve come across that assume a person must either love or hate 2001: A Space Odyssey, with both extremes standing as proof of a person’s intelligence/idiocy with regard to the best/worst examples of brilliance/dreck that sci fi films have to offer. I’ve never understood the obsession with that dichotomy. It’s such a crushingly dull way to look at any movie, or any work of art in any medium. There are much more interesting things to talk about.

Let’s start with where the film came from, because the origin is charmingly mundane: Stanley Kubrick really just wanted to make a sci fi movie. He didn’t know quite what he wanted to say, he didn’t have a story in mind; he just knew he wanted to make a big, serious sci fi film.

He had finished Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), a satire about nuclear war that is at least sci fi-adjacent, as it’s not really possible to separate the political films of the atomic era from the speculative aspects of their themes and impact. And for his next project, he wanted to make a pure sci fi movie, and he wanted it to be good. Kubrick first got onto the idea of making a sci fi movie because he was interested in the possibility of intelligent extraterrestrial life, and even more than that, he was interested in how the existence of such a species would impact humans. (That link goes to an excellent 2018 Vanity Fair article about the making of 2001; I recommend it for anybody interested in more detail than I can fit here.) His goal of making a good sci fi movie seems to have meant serious, thought-provoking, and meaningful, but also well-made in the technical sense, with a big budget and a high level of craftsmanship.

We’ve watched enough movies by now to recognize that by the mid-1960s, cinema was already embracing serious, thoughtful sci fi movies that were trying to say something about humanity. A few of the mid-century films we’ve watched fit that description: The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Godzilla (1954), Alphaville (1965), and of course Ikarie XB-1 (1963), which some writers have suggested might be among Kubrick’s direct influences. Even before the Space Race got underway, sci fi cinema had been playing around with how to portray more realistic space travel, even in more adventure-driven films. Two movies about manned expeditions to space, Kurt Neumann’s Rocketship X-M (1950) and George Pal’s Destination Moon (1950), were produced and released at the same time, five years before the U.S. and the Soviet Union publicly declared their intentions to launch artificial satellites into Earth’s orbit.

There isn’t a list of the sci fi Kubrick watched and read when he was making 2001, but he certainly did go on a wide-reaching and unrestrained sci fi film binge during the years of the movie’s conception and production. In a 1966 profile in The New Yorker, the reporter writes, “Kubrick told me he had seen practically every science-fiction film ever made, and any number of more conventional films that had interesting special effects.” That was how he worked: once he became interested in a subject, he immersed himself in it.

And when Kubrick began looking around for a writer to work on the screenplay, somebody suggested he seek out Arthur C. Clarke.

Kubrick and Clarke met in 1964 and spent the next few years working together on both the film and the novel, although their partnership was sometimes contentious. Clarke offered a handful of his stories as potential source material, and over time they cobbled together several ideas to come up with a plot. The two Clarke stories most obviously represented in 2001 are “Sentinel of Eternity,” which is about scientists discovering a mysterious alien structure on the Moon, and “Encounter in the Dawn,” which is about space explorers traveling to a planet and meeting a primitive species who are revealed to be early humans. (I recommend following that second link just to read the editorial note that accompanies Clarke’s story in that 1953 issue of Amazing Stories. Publishers just don’t hype up stories with lines like “Gets better results than anything by the boom-boom boys” anymore.)

The elements taken from those two stories are easy to recognize in the film. Overall, I think it’s pretty easy to see that 2001 is a film made up of cobbled-together pieces of stories and ideas that were worked and reworked and reworked again countless times over the years the movie was in production. The story of this movie’s prolonged production is pretty legendary in film history: it was delayed numerous times, it cost a huge amount of money, and several people would go on to say that it was the most challenging production they ever worked on.

Some of the changes made en route to the final film seem a bit silly or quaint in retrospect. At one point there was a narrative voiceover, but that got cut out, along with most of the dialogue. Kubrick decided fairly early on that he wanted the movie to be, as he said in a 1968 interview with Playboy, “a nonverbal experience.” There was an early plan to open the film with interviews with real-world scientists. The plot went through variations where there was a stronger emphasis on the Cold War politics of the day. Sometimes the mission was to Saturn, not Jupiter. Many of these elements were changed before filming, but some—like the removal of most of the dialogue—came quite late in the process.

The novel was written concurrently with the film, with a constant push and pull between the two; Kubrick believed a story with such big ideas was better hashed out in prose, but Clarke grew frustrated with Kubrick’s constant changes. (Nearly all of Kubrick’s films are adaptations of prose fiction.) Kubrick and Clarke’s initial treatment for the film—which was a whopping 250 pages long, roughly 50 times longer than a film treatment ought to be—contained no trace of HAL 9000 and the related drama during the Jupiter expedition.

The shooting script used for the film didn’t even describe the ending. This is what it said: “In a moment of time, too short to be measured, space turned and twisted upon itself. THE END.”

The film evolved constantly throughout its production, and the trend was consistent: every change was made to make the themes bigger, the meaning more abstract, and the overall experience more challenging for the audience.

Let’s be completely clear: this is not normally how big-budget, major studio movies are made. Maybe—maybe—this is more common for arthouse films, but it is so far from how major studio films are made that it’s astonishing the movie got made at all.

Ever since the advent of sound movies and the era of the Hollywood studio system, movies from major studios have been expected to, at they very least, know what direction the story will take and how it’s going to end before they start filming. This isn’t even how movies were made during the 1970s era of indulging and encouraging up-and-coming young filmmakers to go wild with their best ideas. Bruce Handy, in that same 2018 Vanity Fair article, describes it as “a feat of sustained innovation, even improvisation, led by one of the most controlling and obsessive directors in movie history.”

This goes far beyond eschewing the use of storyboards (such as Terry Gilliam does with his films, including 12 Monkeys) and it goes far beyond reshooting and editing right up until the last possible moment (such as Steven Spielberg did with Close Encounters of the Third Kind). Very few productions of any scale can afford the time or money required to approach filmmaking in this manner, and even fewer would manage to come up with something coherent and interesting as the end result. It only happened because Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer was willing to let Kubrick take the time and money he needed to figure it out. It was one of the more insane wagers in film history, made by Robert O’Brien, president of MGM at the time, who approved the project based on Kubrick’s reputation and that 250-page treatment, without knowing how the special effects would be accomplished, without knowing how the movie would end, and without ever pulling the plug through countless delays and missed deadlines.

Movie people like to throw around the word “visionary” a lot, but I think this is one of the rare cases where it is truly applicable. This movie exists because Stanley Kubrick had a vision of a story he wanted to tell. That vision changed significantly as he was telling it, so much so that it can be amusing to compare ideas from early in the planning to things he said about the film after it was finished.

The best example of this has to do with the aliens in the movie. “Uh, what aliens in the movie?” you might ask, because we all know the aliens never actually show up on screen. We only ever see their black monolith. But that wasn’t always going to be the case. Early in pre-production, Kubrick and Clarke knew they needed some help visualizing highly advanced extraterrestrials, so they asked Carl Sagan. Sagan suggested they might want to hint at the aliens rather than show them directly, but Kubrick still went through several iterations of possible on-screen aliens before finally opting for the suggested-but-never-revealed route taken in the final film. According to production notes, the ideas for the aliens included a highly advanced city, robots, “squat cones with tube-like legs,” and “elegant, silvery metal crabs supported on four jointed legs.”

Let’s all take a moment to imagine 2001: A Space Odyssey with metal crab aliens.

I very much recommend the entire 1968 Playboy interview with Kubrick, because I think it explains what he wanted to achieve with 2001 and its aliens better than any number of critics, scholars, or random people who write about sci fi movies on the internet (i.e., me). This is what he says when speculating about how ancient extraterrestrial species might have evolved:

“They may have progressed from biological species, which are fragile shells for the mind at best, into immortal machine entities—and then, over innumerable eons, they could emerge from the chrysalis of matter transformed into beings of pure energy and spirit. Their potentialities would be limitless and their intelligence ungraspable by humans.”

The idea of aliens so advanced they appear god-like to our limited human comprehension is very common in sci fi. (I personally do not think this is a bad thing, because it’s a trope I love.) And in a visual medium there will always be a question about how to portray such aliens. Different stories offer different solutions; a common approach is to have the aliens take on the guise of a person, such as in Contact (1995), which we’ll watch in a couple of weeks, or in the case of Star Trek: The Next Generation’s Q Continuum.

2001 opts not to not show them at all, in any form, but to instead show us only what the lone unlucky guy caught up in their shenanigans experiences. I have to be honest here: I don’t find the trip through the so-called Star Gate to be terribly convincing. Part of that is just an unfortunate artifact of the passage of time, because by the time I saw the film humanity had already entered the era of its evolution that included Windows 95 screensavers, which is what the Star Gate journey reminds me of. But of course, the movie was made before computer effects were possible; it was made when even high-quality astrophotography was hard to come by.

So that sequence had to be done the old fashioned way, by which I mean: brainstorming some ideas with moldy vats of chemicals in an old bra factory and letting 23-year-old Douglas Trumbull, brand-new to the special effects world, figure out a way to combine streak photography with slit-scan animation to approximate the psychedelic sensation of traveling through incomprehensible space and time.

I admire the creativity and technical skill required to film such a scene in the 1960s, and I appreciate it for the impact it has had on how we visualize an inherently un-visualizable concept… but I still think it looks like a Windows 95 screensaver. Such are the disappointments of progress.

This is, by the way, not remotely true for the rest of the movie’s special effects. They hold up brilliantly, a credit to the numerous exacting methods the crew used to the create them. One thing I really like about 2001 is that, while it’s about these big ideas about the nature of humanity and our place in the universe, it is at the same time a reminder that movies, as a storytelling medium, are a very physical thing, made up of thousands of individual elements that exist in the real world. Oh, sure, we could quibble about what that means in the era of computer animation, but right now we’re talking about a movie made in the 1960s, for which every aspect was painstakingly constructed and filmed to create as immersive and complete a setting as possible.

I’m not going to get into everything; we would be here forever. The people involved in the production were and are, rightfully, incredibly proud of what they achieved, and have spent decades more than happy to talk about how they achieved it. (This is one of my favorite things about special effects folks in the movie business: they want to tell everyone how they do what they do.) The apes in the desert are convincing (and played by a professional mime troupe, with mime Daniel Richter as the lead ape), the monolith is strikingly ominous, the PanAm spaceplane and the space Howard Johnsons are charmingly mod, and all of it looks great, even decades later. The miniatures are especially fantastic; it’s easy to see why their design and level of detail set an industry standard.

Kubrick was, by all accounts, obsessively demanding and exacting about the movie’s effects. The filming of all the actors (at least those who didn’t wear ape suits) finished in 1966, then the crew spent roughly another 18 months working on the special effects scenes. According to the Vanity Fair article, one challenge was the fact that Kubrick didn’t want any degradation in the image quality when the layers of each scene were composited, so every aspect of the scene was shot on the same film negative. That is: if a scene features, for example, the actors, a model or miniature, and perhaps a view of the stars or a planet through a window, each element was filmed separately, but on the same negative. Because of the lengthy production timeline, sometimes there would be months or longer between the filming of one layer of a scene and the next.

That is a big part of why 2001 still looks so fabulously crisp and clean, but it also meant that if anything was even slightly misaligned, such as the model window and the view through it not quite matching, the entire scene—every element—had to be filmed over again. You can read more about the insane level of technical precision required to achieve this in an article Trumbull wrote for American Cinematographer (subsequently archived in a few places online).

I know I have said this before about other movies, but it bears repeating: This is a completely insane way to make a film.

And it was only possible because Kubrick was able to take the time, spend the money, and maintain the absolute control that he wanted and needed.

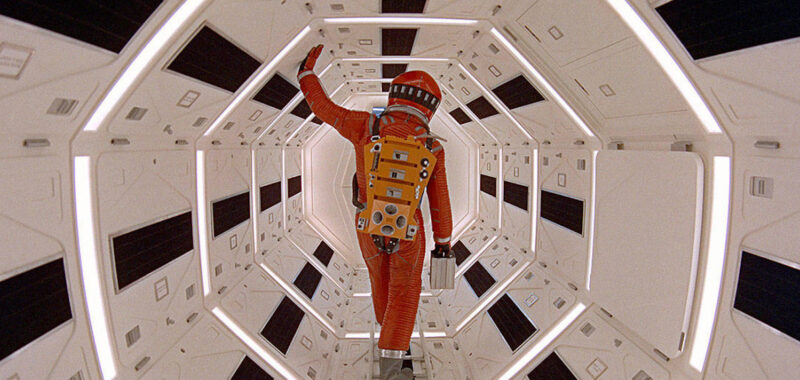

That, and the resources to build an entire set into a 40-foot-tall, 40-ton centrifuge capable of rotating continuously at up to three miles per hour.

The Jupiter mission is my favorite part of 2001. I think it’s the best and most effective section of the movie, because it’s the most immersive. I don’t mind the slow opening in the desert as much as all the moviegoers who walked out of the film when it premiered, nor am I put off by the very sedate build-up to revealing the monolith on the Moon and that terrible screeching that my cats hate so much. There are moments of emotional engagement—the hominid apes going, uh, ape-shit on each other is unnervingly violent. But for the most part I can see why others might find those sequences boring, even though I don’t find myself bored so much as gently detached.

That all changes when we get aboard Discovery One. The abrupt shift from the screaming monolith to the uncanny quiet and uncomfortable geometry of the ship’s living quarters is surely one of the most effective and jarring scene changes in film history. Suddenly we’re in a situation where the scale is more confined and personal, everything is clean and functional, but nothing about it feels soothing or reassuring. The bleakly normal parental birthday message from Earth, the boring workout, the awkward press interview that’s more interested in HAL 9000 (wonderfully voiced by Douglas Rain) than in the fact that humans are going to Jupiter, the eerie presence of the hibernating crew members, the heavy quiet between David Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) that suggests colleagues who exhausted all possible casual conversation several months ago… all of this combines to create a wonderfully unsettling atmosphere.

The use of an actual rotating set—look at photos, it’s such a cool contraption—helps with the sense of realism, but that feeling of wrongness comes from how Kubrick and cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth use that set. The earlier spaceflight, hotel lobby, and conference room were designed and filmed to show humans carrying their aesthetics of comfort and civility into space, to establish a degree of misleading mundanity to what’s happening on screen. But life aboard Discovery One is different, with the constant motion, the odd and unnatural camera angles, the scenes where the actors had to be strapped in and the props glued down, and, of course, the intermittent HAL’s-eye view.

Here, the long scenes and long silences feel not indulgent but ominous. The dialogue and sound design are especially important. The familiar classical music is replaced by very little music, a few carefully chosen sounds, and conversation that is concealing more than it reveals. That fact that HAL has a warm, human voice and natural speech patterns only highlights how uncomfortable the silence and other sounds are. By the time we reach the point where the only noise is Poole’s breathing in his spacesuit, we’re already on edge. It’s grating, it’s relentless, and the tension never lets up.

This is why the Discovery One section is my favorite part of the entire movie, the one part that I do truly love. It’s that part that makes me forget that I’m watching a movie, and instead feel like maybe I’m about to die horribly in space. To be alone in space, millions of miles from Earth and any possible help, on a mission you don’t fully understand, aboard a ship that is actively trying to kill you, hurtling toward a fate you can’t even comprehend—this is my favorite kind of science fiction, my platonic ideal of what I want from stories about traveling into space. I want everything to be terrifying.

Overall, I guess I would say that I find many parts of 2001 genuinely brilliant, but other parts don’t quite have the same impact, and as a whole it is an ambitious and fascinating but flawed and uneven work. But such a summary is pointlessly reductive, because the question of “Is it good or does it suck?” is the least interesting way to approach any movie, and especially a movie like this. I know that our modern capitalist hellscape of nonstop commentary and rapid-fire judgement wants us to believe otherwise, but art does not, in fact, exist only to be judged as good or bad by people on the internet.

I want sci fi films to be big and weird and ambitious, even if they don’t fully work. I want sci fi films to make us feel uncomfortable, uncertain, and unsettled. I want there to always be room for sci fi stories that have absolutely nothing to do with traditional narrative heroism, and instead go off on wild tangents exploring what it means to be a very small species in a very large universe. I want this even if—especially if—those films don’t always work, aren’t anywhere near perfect, will inevitably be hated by some and adored by others, and can’t ever be fully explained or replicated.

After all, what is science fiction even for if not to attempt to tell stories about incomprehensible experiences and extravagant ideas in ways that can’t be captured through mundane human experience? I’m glad that 2001 exists, because I’m glad for the way it blew open the possibilities of sci fi storytelling in film all the way back in 1968. But I’m also glad it remains every bit as odd, impenetrable, and divisive as it was more than half a century ago.

What are your thoughts about 2001: A Space Odyssey and its place in sci fi history? How suited are movies to telling stories about sci fi’s big themes and complex ideas? Would you ever do an EVA without a tether tying you to your spaceship? I wouldn’t. I want space to be terrifying—but not that terrifying.

Next week: This week. things ended poorly for the relationship between humankind and our machines, so let’s see how it fares in Ghost in the Shell (1995). Watch it on Amazon, Hoopla, Tubi, Apple, Microsoft.